Getting Ready for Irrigation Scheduling: A quick overview

With an exceptionally dry winter behind us we are looking at a season in which irrigation is likely to bring a good return on investment. As anybody who schedules irrigation knows, the trick to getting the most benefit comes down to first timing and second to putting out the proper amount. The goal is to prevent yield loss from drought stress while avoiding wasteful application of irrigation water. Unfortunately, by the time crop stress becomes visible, yield has already been affected. So in order to make the best of irrigation one has to make the decision to irrigate based on monitoring or estimating how much water is available to the plants.

Here is a quick overview of the three main factors one needs to consider before making the decision to irrigate:

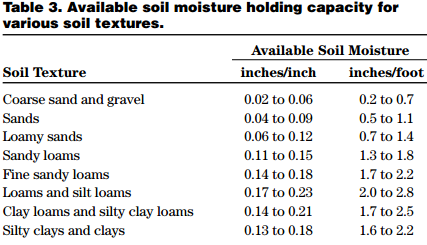

- Plant available water holding capacity for your soil in the effective root zone. (depends on crop): This tells you how much water is available to plants at field capacity. One can get a good estimate of it based on soil texture (https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/ageng/irrigate/ae1675.pdf). Most county soil surveys also give that information listed as “available water capacity” in the data table named “physical and chemical properties of soil”. There are also in-situ and laboratory methods that can be used for greater accuracy.

Figure 1. NDSU Extension Service Publication: Soil, Water and Plant Charcteristics Important to Irrigation (2013) Revised by Thomas F. Scherer, David Franzen and Larry Cihacek - Actual amount of plant available water (PAW) in the soil: there are several ways to monitor this. Two of the more affordable, simpler methods are the feel method and the checkbook method, which are especially effective when used in conjunction with each other.

With a bit of practice, soil moisture content can be determined pretty accurately. Here is a picture guide to that method from the USDA: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs144p2_051845.pdf. To use it, one must first know the soil texture of each depth sampled.

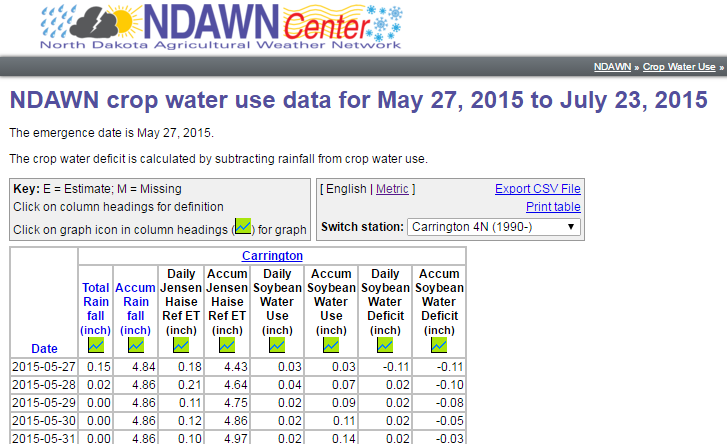

The checkbook method involves calculating crop water use based on weather data and monitoring precipitation on a daily basis. The grower must first determine the amount of plant available water at the beginning of the monitoring period. Then the crop water use would have to be subtracted from the plant available water of the previous day, consequently irrigation and precipitation water would be registered as increases in PAW. Here is a detailed guide from NDSU on how to do that: https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/irrigation/documents/AE-792.pdf. Thankfully, in North Dakota our job is made a little easier by the North Dakota Agricultural Weather Network (NDAWN) service which offers crop water use calculations online for 10 different field crops based on weather data. The user must only specify the area, the crop and the date of emergence to get daily values of crop water use. PAW can also be monitored with other methods, for example by using electric sensors, tensiometers, or by using a neutron probe.

- Management allowable depletion: Once we know how much water is available to our crop, the decision to irrigate comes down to crop water needs and economics. Irrigation is costly and the capacity to irrigate may be limited. A certain amount of PAW can be allowed to be depleted before irrigating up to field capacity without causing yield loss. Usually this is around 40-50 % PAW depending on crop and soil texture. If water is limited during the season, then one should prioritize irrigation during the more sensitive growth stages, usually the reproductive stage, and allow for some level of water stress during the less sensitive periods when yield is less likely to be affected.

Szilvia Yuja

Agronomy Research Specialist