Center Points

What’s Going On in the Greenhouse?

CREC is fortunate in that it has access to a state-of-the-art greenhouse facility. This means that crops research can continue even when there is snow outside (Figure 1). This space has been utilized for various projects over the years, but here is a look at a few projects occurring this winter.

Figure 1. Greenhouse complex utilized by the Carrington Research Extension Center.

Figure 1. Greenhouse complex utilized by the Carrington Research Extension Center.

Cover crop tolerance to residual herbicides. The objective of this study was to grow numerous cover crops and document injury symptoms from herbicide carryover. In this study Pursuit, Widematch, and Acuron were applied at 3 micro-rates of each product ranging from 0.5x, 0.125x, and 0.03x of field use-rates. Eight cover crop species were weighed and photographed at the end of the study.

Rye allelopathy to cash crops. This study was designed to try isolate allelopathic properties of rye from competitive properties. Two rye varieties and one winter wheat variety were tested together (same pot) or separate (2 pots, but same area as 1 pot) from sunflowers, soybeans, and flax. Preliminary results indicate that sunflower biomass was reduced 26-30% when grown together with rye (compared to grown separately). Winter wheat reduced sunflower biomass by 16%. Winter wheat reduced soybean biomass more than the two rye varieties (22 vs 10% reduction) when grown together. Flax saw a flax 14% reduction regardless of cereal companion.

Evaluation of flax variety tolerance to fusarium wilt. The objective of this experiment is to assess the tolerance of 10 flax varieties to fusarium wilt. Fusarium wilt is a seedling disease of flax that often is overlooked as producers implement flax production practices. Most flax varieties are rated as moderately resistant (MR) to the disease. However, in 2020 we observed high levels of infection among varieties within the variety trial, many that are rated as MR for the disease. This greenhouse trial is our attempt to provide additional information related to how different flax varieties tolerate potential infections due to fusarium wilt. Figure 2 is a display of flax disease response occurring in the greenhouse.

Figure 2. Flax displaying disease symptoms in the greenhouse.

Figure 2. Flax displaying disease symptoms in the greenhouse.

Sorghum improvement. Sorghum germplasm has been grown in field studies near Carrington since 2016. The best performing lines are being crossed in the greenhouse to develop some northern hardy sorghum varieties.

Cover crop precision agriculture. Cover crop species are being screened for tolerance to soil characteristics typical of topography change in North Dakota. Six samples of soil were taken across an elevation gradient which differ in CCE (calcium carbonate equivalency). The controlled setting of the greenhouse allows us to remove moisture differences from the screening process to determine which cover crops respond to changes in soil carbonate concentrations.

Mike Ostlie

Mike.Ostlie@ndsu.edu

Assistant Director and Agronomist

Blaine Schatz

Blaine.Schatz@ndsu.edu

CREC Director and Agronomist

Is Your Ranch Prepared for Drought?

About 85% of North Dakota is experiencing some level of drought and many ranchers are concerned the drought will extend into the 2021 grazing season.

North Dakota State University Extension specialists, including Miranda Meehan, Kevin Sedivec, Gerald Stokka, Janna Block, Karl Hoppe, Lisa Pederson and Sean Brotherson, have been hosting live webinars to assist ranchers as they prepare for drought. The series continues with this week’s session at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time on Thursday, Feb. 25.

Miranda Meehan, left, and Kevin Sedivec, right, visit with ranchers during the February 18 session of Preparing Your Ranch for Drought.

Miranda Meehan, left, and Kevin Sedivec, right, visit with ranchers during the February 18 session of Preparing Your Ranch for Drought.

“This webinar will give North Dakota ranchers a chance to learn about different drought management strategies that will aid them in developing a drought plan for their ranch, as well as give them an opportunity to discuss drought-related concerns,” says Miranda Meehan, NDSU Extension livestock environmental stewardship specialist.

Two sessions have already been hosted and recorded:

- Thursday, Feb. 11 - drought outlook

- Thursday, Feb. 18 - drought trigger dates and grazing strategies

Remaining sessions are:

- Thursday, Feb. 25 - supplemental feed and forage options

- Thursday, March 4 – water supply and quality

- Thursday, March 11 - herd management and reduction strategies

- Thursday, March 18 - managing stress during drought

“It is important that ranchers have a drought management plan in place early so they are prepared and able to make timely decisions if drought persists,” Meehan says.

To register for the webinar, visit https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/drought/preparing-your-ranch-for-drought-webinars .

Participants may ask questions during each live webinar. Each session will be recorded and the recording will be archived at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/drought/preparing-your-ranch-for-drought-webinars for later viewing.

The Preparing Your Ranch for Drought sessions are part of a broader effort by NDSU Extension to develop and update resources to help farmers, ranchers, homeowners, horticulturalists, and gardeners cope with conditions. Additional topics are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/drought.

Mary Keena

Mary.Keena@ndsu.edu

Extension Livestock Environmental Management Specialist

Pears at the CREC Orchard

In 2015, we selected six ‘very hardy’ varieties of pear from St. Lawrence Nursery to find out how they grow in North Dakota and planted two of each at 15’ x 20’ spacing.

In typical loam soil, these trees will really grow. I try to prune these lightly; not as much as an apple tree, because pruning just invigorates growth. Pears can grow into very large trees. In 2019 and 2020, when the trees grew as high as I could reach on a ladder, I cut back the leaders to a side branch. We will see if this was a good idea or not. If you want to grow pear trees (you typically need two varieties to get fruit), I recommend that you love pruning.

For the most part, the trees grow with narrow crotch angles. I use wooden lath to make spreaders and these trees end up looking like art projects, according to my husband. Some of the varieties produce water sprouts that can grow five feet in one season. I remove these but try to leave other branches that I normally would have removed in an apple tree. I also cut back by half some of the branch tips that have grown 2-3 feet. I want to make sure that we get sort-of compact growth. Sometimes I do this in spring. Sometimes I try it in summer.

Using spacers to create better branch angles.

One variety, ‘Ayers,’ failed after several years due to cold injury and I removed it. The precocious (fruit-bearing at an early age) variety, ‘Schroeder Hardy ND’, had fruit in its third year (just 3) and has produced every year since. One of two trees of the remaining varieties all had some fruit this past year, although ‘Patten’ had just one fruit.

With pears, you have to pick the fruits when they are ready but not ripe. This means watching and then picking the fruit when it reaches a certain stage: generally, when the fruit color changes from dark green to light green and the lenticels turn brown. Then that fruit is stored in a way that the starch granules can change into sugars. For ‘winter’ pears, like commercial ‘D’Anjou’, this means three months of cold storage before they can ripen at room temperature. For summer pears like ‘Bartlett’, it takes just three weeks of storage. (Therefore, never buy US ‘Bartlett’ after Christmas or ‘D’Anjou’ before.) The tricky part is finding out the proper storage conditions. Is it in the refrigerator, or ‘cool’ temps, or room temp? And for how long?

Pears in August

So far, I have not been able to figure out how to ripen ‘Schroeder Hardy ND.’ It spoils from the inside out every time. There was no chance to figure it out for the other varieties this year either – a very windy night on September 2 caused all the pears to fall off the trees before they were ripe. I’m afraid that this will be a problem in North Dakota – that the stems connections are very brittle and the pears easily fall in the wind. We’ll know more after 2021, I hope.

Kathy Wiederholt

Kathy.Wiederholt@ndsu.edu

Northern Hardy Fruit Project Manager

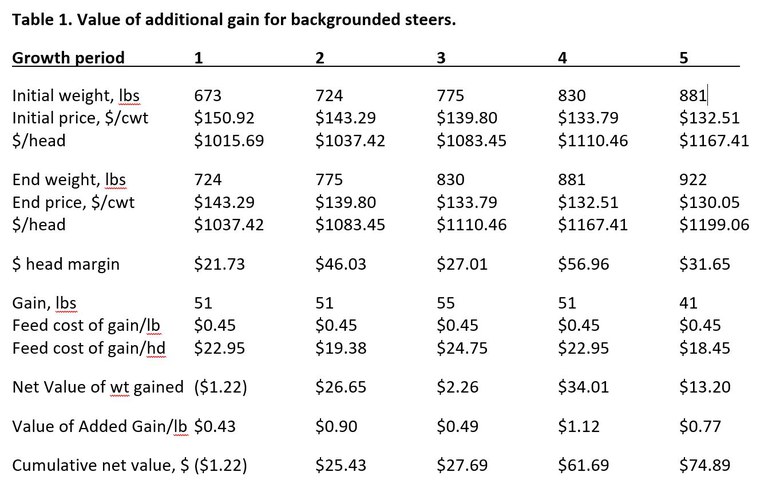

The Value of Additional Gain for Backgrounding Cattle

Most calves change ownership two or more times in the production cycle. The cow calf producer usually sells at weaning or feeds the calf after weaning and sells a short time later. The backgrounder (or stocker) will feed calves for 60 – 200 days before selling to a finishing feedlot.

Backgrounders can influence the amount of weight gained by a calf depending on feed prices and market prices. Ultimately, it’s the cost of gain that determines what ration is fed.

- Calves gaining 1.5 pounds per day with $75 per ton hay and $75 per ton screenings net a feed cost of $0.45 per pound gained.

- Calves gaining 3 pounds per day with $75 per ton hay, $40 per ton silage and $4.75 per bushel corn net a feed cost of $0.38 per pound gained.

These costs are feed only and don't include yardage or interest expenses.

Estimating future value of calves is difficult with changing economies and variable feed costs. Unless calves are forward-priced or hedged, we use historical trends and biology to help forecast future prices.

This leads to calculating the value of additional gain. For these calculations, the USDA prices reported for ND Livestock Auctions were used and it located at Weighted Average Report (usda.gov).

In this example, the value of additional weight was greater than the feed cost of gain in the heavier weight periods. Cumulative net value increases as weights increase.

If market price decreases $4/cwt among all prices except the beginning market price, then the cumulative net value decreases from $74.89 to $38.01. When feed prices are high, adding value to calves by feeding to heavier weights is profitable when not including yardage costs.

When yardage costs are added at $0.45 per head ($0.15 per pound gained), the cumulative net value decreases accordingly. With decreased market price and increased yardage, cumulative net value further decreased from $38.01 to $15.49.

Feeding to heavier weights is cost effective with these prices. However, low cost feeds, reduced yardage expenses, and superior performance improve profitability.

Karl Hoppe

Karl.Hoppe@ndsu.edu

Extension Livestock Systems Specialist

Dry Bean and Soybean Getting-It-Right Virtual Meetings in February

Farmers and crop advisers will have an opportunity to receive dry edible bean and soybean production information during virtual Getting-It-Right production meetings. NDSU Extension is organizing and conducting the meeting in cooperation with the Northarvest Bean Growers Association and the North Dakota Soybean Council.

Proper plant establishment is critical to a successful harvest.

“The webinars will provide concise presentations to reach dry bean and soybean producers, and crop advisers with research-based production recommendations for 2021,” says Greg Endres, Extension cropping systems specialist based at NDSU’s Carrington Research Extension Center.

The dry bean meeting is scheduled at 9 a.m. to noon, Tuesday, Feb. 2. Subjects that will be covered and presenters are:

- Market types and variety review - Hans Kandel, Extension agronomist

- Recommendations for selected plant establishment factors – Endres

- Soil considerations and plant nutrition - Dave Franzen, Extension soil science specialist

- Insect management - Janet Knodel, Extension entomologist

- Disease management - Sam Markell, Extension plant pathologist

- Weed management - Joe Ikley, Extension weed specialist

Also during the dry bean program, Mitch Coulter, Northarvest executive director, will provide an update of the organization. In addition, a prerecorded video that provides a dry bean market update by Frayne Olson, Extension crops economist, will be available.

The soybean meeting is scheduled at 8:30 to 11 a.m., Wednesday, Feb. 17. Subjects that will be covered and presenters are:

- Soybean maturity and planting date - Bryan Hanson, research agronomist, NDSU Langdon Research Extension Center

- Variety selection, the benefits of combining early planting, a late maturing variety, seeding rate and row spacing, and the results of a study evaluating foliar application of nutrients – Kandel

- A large row spacing and seeding rate study and the effect of cover crops in the soybean system – Endres

- Midges in soybeans and a 2021 insect pest forecast – Knodel

- Newer soybean diseases found in this region, such as frogeye leafspot, and an update and management recommendations on several important plant diseases - Markell

Participation in the meetings is free of charge but preregistration is required. Visit https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/carringtonrec/events to view the schedules and preregister. Those who preregister will receive emailed instructions to participate in the meeting.

Presentations will be recorded and archived. Certified crop adviser continuing education credits will be available for meeting participants.

Greg Endres

Gregory.Endres@ndsu.edu

Extension Agronomist

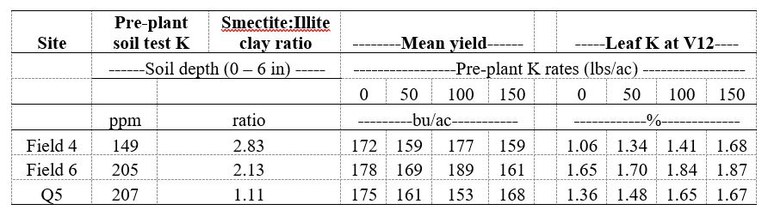

Failure of potassium fertilization to impact corn yields at Carrington—why?

The revised potassium (K) fertilizer recommendation for corn in North Dakota shows that yields will unlikely be impacted by K when soil test levels are greater than 150 ppm and the soil contains high amounts of illite clays, or the ratio of smectite clay to illite clay is < 3.5.

Field trials were conducted to determine if K soil test and clay are low for three Carrington research fields to for K recommendation purposes. Trials were established on three fields (Field 4, Field 6, and Q5) at the Carrington REC and fertilized with pre-plant K at 0, 50, 100, and 150 lbs/ac, and top-dress K at 40 lbs at V4, V8, and V12, respectively. Soil K and clay types were analyzed.

Corn did not show K deficiency at any of the three sites, suggesting K was not deficient. As a result, yields did not improve from K fertilization even though leaf K concentration was significantly greater for the K fertilized treatments - an evidence of luxury consumption of K from fertilization (Table 1). Leaf K was also increased by top-dressing corn with K at V4 and V8. The lack of K impact was likely due to adequate soil K present in readily available form or supplied by the clay minerals.

It should be noted that soil tests can sometimes show low available K but the crop does not respond to K. This often happens because K bound to illite clay is usually not accounted for during routine K analysis; yet, it can be released from the clay and become available for root uptake.

Table 1. Soil analysis of K, smectite and illite clay ratios, and mean yields and leaf K concentration of corn in response to potassium fertilizer application on three fields at the Carrington REC.

Why is it that some years, K deficiency sometimes appears on corn at these sites even though soil K may be adequate (150 ppm), or has high illite clays, or low smectite:illite ratio? Because of drought. Soil moisture is needed for K to dissolve, to stay in available form, and to be moved by rain. Unlike very mobile nutrients like N and S in soil, K has very low mobility. Thus crop roots need to grow beyond their immediate vicinity (where nutrients may have been depleted) in order to have access to the less mobile nutrients like K and P. Soil moisture helps to move dissolved K closer to roots. When the soil is dry for prolonged periods, soil test of available K probably needs to be greater than 150 ppm.

Conclusion: Potassium fertilization is not recommended for the Carrington REC field plots, unless for corrective measures, when the crops express deficiencies during drought conditions. It is important to soil sample and test for K to help determine future course of action. Further reading in the Crop and Pest report (https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/cpr/soils/potassium-deficiency-in-season-diagnosis-and-correction-in-corn-07-11-19).

This research was conducted with funding from the North Dakota Corn Council.

Jasper Teboh, Ph. D.

Jasper.Teboh@ndsu.edu

Soil Scientist

Meeting You Where You Are, Online

More than 4,600 NDSU Extension program sessions were held in 2020, reaching in excess of 304,000 participants. That was no small feat, especially when considering 37.5% of the programs were held either strictly online or in a combination of online and face-to-face.

The sudden change to virtual platforms (programming, meetings, strategy sessions, grant presentations, advisory board input sessions) in March 2020 required all of us at NDSU, including CREC staff, to learn some new tricks – even the old dogs! Our living rooms, spare bedrooms and basements were quickly turned into offices. We invited our colleagues and constituents into these personal spaces and we kept working. Field plans were finalized, research proposals submitted and educational programs shared.

We found ourselves rethinking many of our programs and how we share information with you. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. Moving things to an online format really made us think, “What’s important here?” and “What do we really want people to learn, know, and be able to implement right now in their operations or in their lives?”

Moving to an online format was mentally draining at times but it also helped us answer the question, “Why are we doing this?” Ultimately, if a program, meeting or strategy session was held, it was because we really, really thought it would be important for you to have the information.

As we move back to a mixed model of face-to-face and online programming, we will continue to ask those important questions. We don’t want to host a meeting, online or face-to-face, unless there is confirmation from you, our constituent, that it’s necessary and useful.

If 2020 taught us nothing else, it did teach us that time is most certainly precious and we don’t intend to waste it.

As we head into 2021 here are a list of upcoming online meetings and a few previously recorded programs that we think, based on your feedback, will be useful for you.

- Videos from our Virtual Field Day and Crop Management Field School, and Row Crop Tour are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/carringtonrec/videos

- Videos from our Online Manure Composting Workshop are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/lem/2020-manure-composting-online-workshop

- Videos from the NDSU Extension Horse Management Webinars are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/lem/horse-management-webinars

- Videos from the Central Dakota Ag Day are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/carringtonrec/Central%20Dakota%20Ag%20Day

- Videos from this year’s Backgrounding Cattle series are available at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/livestockextension/backgrounding

NDSU Extension Cropping Systems Specialist Greg Endres discussed the 60-species Weed Arboretum as part of the Crop Management Field School video programs.

Upcoming events, mostly online at this point, involving Carrington REC staff, are listed at https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/carringtonrec/events.

Mary Keena

Mary.Keena@ndsu.edu

Livestock Environmental Management Specialist

Organic Cover Crop and Manure Management

A field trial to examine organic cover crop management in combination with animal manure application was conducted from 2007-2011 at the CREC. While this may seem like old data, it’s not! In terms of soil health development, immediate management changes have long-lasting effects.

A full-season cover crop was grown in 2007 to establish the 5-year trial. The cover crop, planted June 7, included a mixture of oats, buckwheat, field peas, and turnips. The cover crop was hayed and bales were removed on August 22, and the green manure treatments were established when the standing crop was disked twice on August 24. The amount of biomass in all treatments was determined to be 3.2 ton/ac DM. Livestock (feedlot cattle) manure applications occurred on August 23 at a rate of 8.3 ton/ac DM.

Biomass sampling in the 2008 organic cover crop manure timing trial.

Biomass sampling in the 2008 organic cover crop manure timing trial.

Table 1 lists the manure treatment descriptions for this trial.

Table 2 lists crop information for each of the years the trial was conducted.

Table 1. Manure treatments

GM green manure cover crop terminated by disk

GM/MAN green manure cover crop terminated by disk with livestock manure application

HAY hayed cover crop

HAY/MAN hayed cover crop with livestock manure application

Table 2. Trial information by year

|

Year |

Crop |

Variety |

Planting date |

Harvest date |

|

2007 |

cover crop |

various |

7-Jun |

various |

|

2008 |

potatoes |

Kennebec |

8-May |

10-Sep |

|

2009 |

wheat |

FBC Dylan |

8-May |

24-Aug |

|

2010 |

oats |

Morton |

27-Apr |

2-Aug |

|

2011 |

peas |

Shamrock |

4-May |

5-Aug |

2008 potatoes in cover crop manure trial.

Differences were detected in potato yields in 2008. The green manure/livestock manure treatment #1 yield was significantly higher than the treatment that hayed the cover crop and did not have a manure application. Total yield followed the same trend although was not statistically significant. The 2008 potato crop was the only irrigated crop in the trial.

Differences in yield and quality were detected in the 2009 wheat crop. Treatments that included manure tended to have a yield advantage and a small increase in grain protein.

Performance of oats in 2010 followed the same trend with the highest yields from the green manure/livestock manure treatment followed by the green manure (only) treatment.

No significant differences in yield were detected in field peas during the final year of this rotational trial. The same trend was evident with pea yields as the green manure/livestock manure treatment had a higher yield compared to the other treatments, but statistically the difference was small.

This trial was conducted on a research field that began transition to organic production in 2004 with the last prohibited substances applied in August 2004. The 2008 potato crop was the first certified organic crop from this field.

Despite slight differences in performance between treatments, this trial illustrates the lasting effect that agronomic practices such as green manure and livestock manure application can have on production in an organic system.

Steve Zwinger

Steve.Zwinger@ndsu.edu

Agronomy Research Specialist

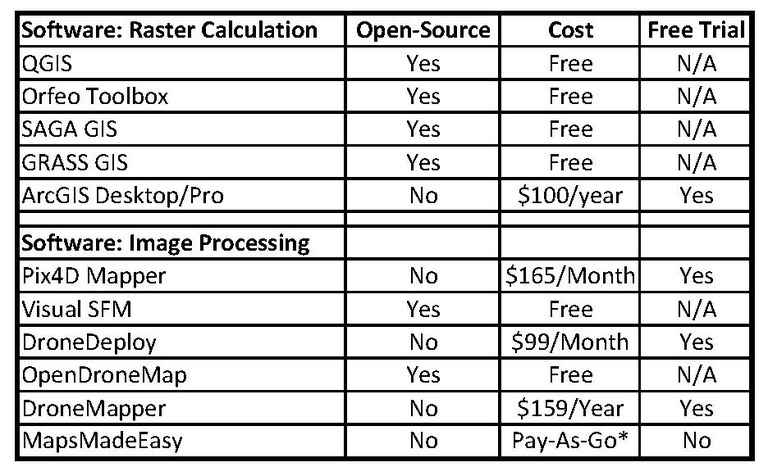

To Fly or Not to Fly: What Role do sUAS Play in Agriculture Today?

The role of small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS) in agriculture has garnered a mixed following over the last few years. Much of the work that has been done, and much of our understanding, has focused on research related projects, which is evident in the relatively large number of scientific journal articles that outline various uses from assessing crop health, to estimating above ground biomass. That said, the role that aerial imagery as a whole has had in agricultural and natural resource applications has long been seen as valuable. For example, the National Agricultural Imagery Program (NAIP) has been in existence since 2003 and represents a federal level program to collect imagery in the Red, Green, Blue, and Near-Infrared (NIR) portions of the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS). This brings us to one of the limiting factors of a typical “affordable” sUAS; the lack of a sensor capable of collecting in NIR, which has formed the basis of nearly all of our “traditional” vegetation index measures due to how NIR interacts with the leaf structure.

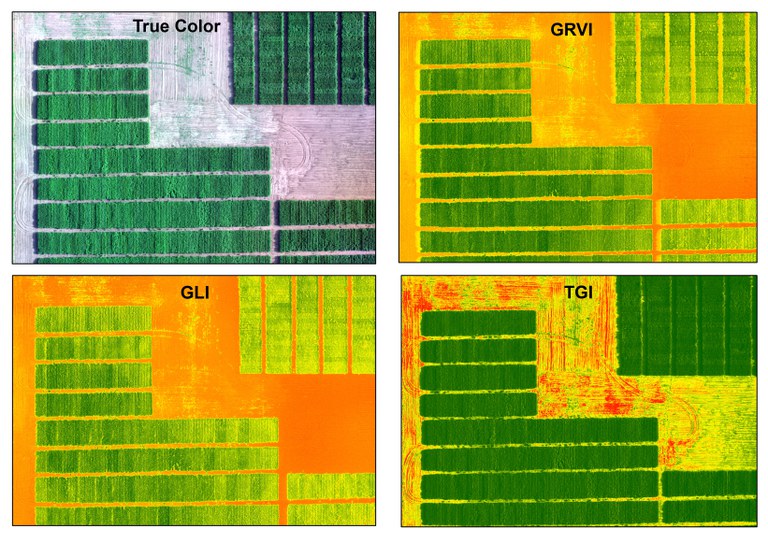

Notwithstanding the lack of NIR sensors, sUAS can provide valuable information with little up-front cost and much has been done to evaluate indexes that use only the visible portion of the EMS. The Green Leaf Index (GLI) was developed specifically for low-altitude crop applications (Figure 1), and others such as the Green-Red vegetation index (Figure 2), and the Triangular Greenness Index (TGI) (Figure 3) have found their place in agricultural applications. Another limiting factor has been the relatively short battery life (~20-30 minutes) for flights. However, with a maximum Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) altitude of 400’, a good deal of information can be collected in that 20-30-minute time span. In addition to the above issues, access to software to process the collected imagery also presents a hurdle. While there are any number of commercial applications out there, there are also low-cost/no-cost options to the average sUAS user for image processing and index calculations (Table 1).

Without question, sUAS have come a long way over the last 5-7 years. We are seeing more affordable airframes, with higher resolution cameras and longer battery life. We have seen advances in image processing algorithms and open source software. And we have seen an increase in interest surrounding non-NIR indexes as applied to agricultural problems. For those that currently have an sUAS, I would recommend getting it in the air! For those that don’t, it might be a worthwhile endeavor to explore what this technology has to offer; it will only get better as time moves forward. A sUAS isn’t the answer to every problem, but it can provide a plethora of information that can help drive decisions regarding nutrient application and prescription maps, and represents another tool in our agricultural toolbox.

Table 1: Sample listing of software available to calculate indexes, and to process imagery. Values range from free open source software, to commercial software at a cost. This table does not represent all of the options available, but rather those that the author has had direct interaction with. Many pay versions offer free trials. The prices listed for commercial software packages are generally considered “personal” use, as opposed to professional.

Figure 1: Three visible spectrum (non-NIR) indexes currently in use for agricultural purposes. Each index has its own strengths and weaknesses. The GLI was developed for low altitude monitoring, making it a good choice for a UAS. The GRVI is a variant of NDVI using the green portion of the EMS instead of the NIR portion. The TGI attempts to measure the reflected light that forms a triangle between the Red, Green, and Blue reflectance measures. The TGI is used to measure estimate leaf chlorophyll content, and has also been used to indirectly measure nitrogen content. All indexes were calculated from a standard RGB camera (e.g. standard camera on the Phantom 4 Pro) requiring no aftermarket costs or alterations.

David Kramar, Ph.D.

David.Kramar@ndsu.edu

Precision Agriculture Specialist

Haskap Selection Research at CREC

Research into varieties of Japanese haskap that do well in North Dakota has been the focus of our project for a few years now. There is only one breeder of haskap in the US and we have been trialing her selections here in what she calls our ‘harsh’ climate (she’s not wrong!). North Dakota’s winemakers absolutely love haskap fruit. Jelly makers should, too, but there is just so little fruit available in the US.

In 2000, Dr. Maxine Thompson, a horticulture researcher retired from Oregon State University whose past research is directly responsible for the current boom in the US hazelnut industry, started breeding and making selections of haskaps from just eight seed sources from Japan. Today, her breeding efforts are finished but the variability she pulled out of those first seeds is amazing. In her orchard, you can find short or tall, upright or weeping, and wide or narrow plants with berries that are tart or sweet, large or small with a wide range of shapes.

Two different shapes of Japanese haskap

I met Dr. Thompson several years after planting some of her first superior selections in 2007. I have been visiting her almost every year since then to see the plants growing and fruiting in her orchard. It is so helpful to see and touch the plants in person because her selection criteria in the Edenic climate of Oregon does not always align with the traits we need here in North Dakota. We really need fruit that clings well and is perhaps not so large so that it can stay on the plants during windy conditions. It also needs to ripen early to avoid SWD damage.

Really huge haskaps at CREC.

In early June this year, as soon as Covid-19 travel restrictions lifted in Oregon, my husband and I drove to Dr. Thompson’s orchard, camping on the way there and back, to stay safe from the coronavirus. It was bittersweet to touch the last plants to emerge from her careful selections of the past 20 years. I made the orchard-wide evaluations, trying to keep true to all I had learned at her side these last years. I am only a small part of this work; her good friend and former student, Shinji, and employee Steve, have done all of the heavy lifting right there at the orchard, year-round, these past few years.

Maxine Thompson, showing my husband one of her new favorite plants.

After evaluating the ripe fruit, I brought back green cuttings and got them started in our greenhouse. My success was so-so, but we can try again this spring with dormant cuttings. We continue to work with other new plants coming into production each year in the CREC orchard.

Japanese haskap cuttings in the CREC greenhouse.

I don’t write about haskap very much because it is hard for the public to buy any varieties that are great in our local conditions. Research and production of other hybrids has been centered in Canada and it is costly to get plants and fruit across the border. If you would like to try some commercially available Japanese haskap plants, talk to your local greenhouses about ordering Proven Winner plants ‘Yezberry Maxie’ and ‘Yezberry Solo’. Also, the newest plants, ‘Maxine’s Opus’ and ‘Kawai’, are available through Gurney’s and Gardens Alive! catalogs and websites. You can also look for other plants at the websites of Haskap Oregon and HoneyberryUSA.

Kathy Wiederholt

Kathy.Wiederholt@ndsu.edu

Fruit Project Manager