Dakota Gardener: Changing of the guard

(Click an image below to view a high-resolution image that can be downloaded)

By Joe Zeleznik, forester

NDSU Extension

The first ones I notice are the sumacs.

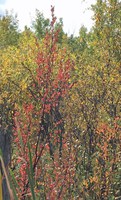

It’s the same pattern each year. Sumacs turn a bright red, and they start changing color early. It’s a bright, fire-engine red, usually. Sometimes they’re a little muted, with a bit of purple mixed in.

Robins are supposed to signal the arrival of spring. For me, sumacs are the first sign of autumn. They’re beautiful.

For the next few weeks, I’ll watch the palette change. In North Dakota, it’s a lot of yellow. You have to search for the reds and oranges, and the occasional purple. But it’s worth it. They’re out there.

In our native forests, red fall colors are found on shrubs and some vines. American cranberrybush, also known as highbush cranberry, is another one that turns a bright red, though it’s much later than the sumac. Highbush cranberry fruit also provides a splash of red in a duller world.

Leaves of Virginia creeper, a common vine, also turn red. The vine snakes its way around tree trunks and up into the crowns, sending a streak of red through a yellow backdrop. It’s beautiful.

As I watch autumn unfold, the old biochemistry lessons come back to mind. The yellows and oranges are mainly produced by carotenoids, pigments that have been hidden all summer by chlorophyll. Photosynthesis uses chlorophyll to capture energy from the sun and turn it into sugar – an amazing process. The carotenoids play a minor role in photosynthesis and become visible once the chlorophyll begins to break down in the fall.

The chemistry behind the reds and purples is pretty remarkable as well. They’re produced by compounds called anthocyanins. These compounds hook up with sugars and then put on a great show. If the cell sap is acidic (low pH), we often see red; if the sap is alkaline (high pH), the display changes to purple. It’s amazing.

Various combinations of anthocyanins and carotenoids can result in yellow, orange and red leaves all on the same tree. A few years ago, I learned about bog birch (scientific name Betula pumila). It’s a small shrub that grows in swamps and, well, bogs! Its colors are subtle but can be orange or red or some combination of them. I look at these unique ecosystems in a whole different way now.

Many landscape painters love autumn. It gives them a chance to explore a whole different palette of color that they haven’t much used for a year. Photographers love this time period as well.

Enjoy the fall colors. Explore and look for the subtle expressions of complex chemistry. We only have a few weeks to enjoy them. Sunny days result in brighter colors. Rain washes them out. And a windstorm can destroy it all, in the blink of an eye.

NDSU Agriculture Communication – Sept. 20, 2022

Source: Joe Zeleznik, 701-730-3389, joseph.zeleznik@ndsu.edu

Editor: Kelli Anderson, 701-231-6136, kelli.c.anderson@ndsu.edu