Spotlight on Economics: Soybean Export Growth Opportunities and Quality

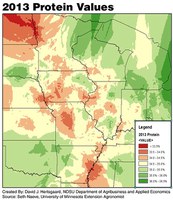

(Click the image below to view a high-resolution image that can be downloaded)

By William W. Wilson, University Distinguished Professor and CHS Chair in Risk and Trading

NDSU Agribusiness and Applied Economics Department

One of the fastest growing markets in the past decade has been that of soybean production and exports. In North Dakota, the area planted to soybeans has increased from about 2 million acres in 2000 to about 5.7 million acres in 2015, and expectations are up to 5.95 million acres in 2016.

Indeed, soybeans have developed from a crop largely grown in southeastern regions to now encompassing most all regions of the state, including most of the west, and all of the counties on the Canadian border. North Dakota also has been the largest exporting state in several of the recent crop years.

China is the dominant soybean importer, with imports growing from nil in years prior to 1997 to now approaching 85 million metric tons (MMT) and buying roughly two-thirds of the world’s soybeans.

For North Dakota, a very large portion of soybeans is shipped by rail to the Pacific Northwest (PNW) for export to China. Soybean exports from the PNW have increased from near nil to approaching 9 MMT in recent years. Indeed, this has been one of the important changes impacting much of the world’s production and marketing.

An important issue confronting exports of soybean is the protein content, which varies across regions and through time. This is important and has governed trade practices in international soybean marketing. Protein and oil content are not included when grading soybeans. However, many buyers have expectations of certain levels of protein and oil content when they purchase soybeans.

Sales contracts for exports to principal buyers typically have protein requirements of 34 percent, with a minimum of 33.5 percent or be subject to discount. Penalties exist for not meeting protein requirements. In addition, contract terms may indicate the shipment can be rejected if quality requirements are not met. It is not uncommon for traders to buy soybeans from North Dakota and, as needed, blend in trainloads of higher protein content soybeans from Nebraska to meet requirements.

Some countries that prospectively would be buyers of PNW soybeans exclude that region as an origin, in part due to perceptions related to quality. Instead, they buy predominantly from the U.S. Gulf region or Brazil. The impact of this results in implicit discounts in the world marketplace for soybeans exported from the PNW.

Traders have indicated that this is in the range of 20 to 40 cents per bushel, which varies through time. Our work has indicated this was closer to 40 cents per bushel a couple of years ago. Taken together, this results in discounts applied to the entire crop region. Another recent study indicted North Dakota producers could see increased revenue of $8 to $13 per acre if this situation were improved.

There is also substantial variation through time and across origins. Data compiled by Seth Naeve, University of Minnesota Extension soybean agronomist, illustrates the spatial distribution of protein levels in the upper central Plains states. It is evident that soybean production in North Dakota has lower protein levels than in parts of other regions.

Lower protein values in the Midwest are thought to be a result of spatially differentiated growing conditions. A major contributor to this is the length of the growing season and the amount of light that soybean plants receive.

According to the data used in our studies, the average protein level in soybeans produced in North Dakota is 34.01 percent. The average protein level of all states is about 34.6 percent. Thus, based on protein level alone, a not inconsequential portion of the crop produced in North Dakota could fall short of requirements or expectations of international buyers.

Although buyers and sellers trade soybean based on protein levels, it is really only a proxy (albeit poor) for ultimate end-use feed value. End users desire higher protein levels due to the nutritional values when used as soybean meal for feed. Soybeans are purchased largely for crushing and eventually utilized as soybean meal for livestock feed.

Sophistication in livestock production has been aided by feeding formulations in which livestock producers aim to maximize growth based on feed inputs. However, feeding formulations are not based on protein values. Rather, formulations aim to maximize the nutritional value based on the proteins’ amino acids.

There are more than 18 different amino acids found in proteins; however, there are only a handful of amino acids that are essential to aid livestock growth. The five amino acids identified as essential for feeding formulations are cysteine, lysine, methionine, threonine and tryptophan. These amino acids are known as the essential amino acids (EAA). Issues related to EAA are a major issue confronting the North Dakota Soybean Council. For more information, visit the reference library section of http://www.soyeaa.com/.

The problem is that the marketing system readily measures protein levels but not the EAA elements. Using EAA to measure soybean quality, rather than crude protein, may lead to a better evaluation of soybean values. Using EAA measurements is important for soybeans grown in North Dakota, where protein values are lower than in other geographical regions. Comparison of these EAA from North Dakota versus other regions indicate that they are similar.

An alternative measure of end-use value in soybean meal, developed by David R. Gast in 2014, is CAAV (critical amino acids value). His results illustrate an inverse relationship between CAAV and protein level. Results from the data analysis indicate that the CAAV from North Dakota soybeans (16.62 percent) are equal or slightly higher than those from comparable regions (16.50 percent).

This is very important for soybean producers and marketers of soybeans. Taken together, it indicates that while selling on protein levels, and prospectively receiving discounts, the greater CAAV values from North Dakota soybeans result in a windfall gain for end users.

The issues here are important for the state’s soybean industry and are one of the strategic initiatives of the North Dakota Soybean Council.

Through time, one would expect that as the market matures, buyers will become more knowledgeable and competition among sellers will intensify. As that evolves, buyers likely will become more demanding, simply wanting to know with greater precision the end-use value of the products they buy. This frequently is referred to as wanting greater consistency in their purchases. The marketing system may respond to this in numerous ways.

Indeed, a major goal would be to increase protein content. In addition, or in the interim, it is essential to have outreach programs explaining these issues, data and the important relationships. Buyers and sellers may respond in a multitude of ways. These may include greater specificity with respect to protein content by ultimately targeting origins, or specifying additional measureable attributes in contracts.

Results of a recent NDSU study, supported by the North Dakota Soybean Council, indicate that greater specificity regarding EAA would result in a slightly higher cost but lesser risk to buyers because the product would meet their expectations of end-use performance.

NDSU Agriculture Communication - April 27, 2016

| Source: | William Wilson, 701-231-7472, william.wilson@ndsu.edu |

|---|---|

| Editor: | Kelli Armbruster, 701-231-6136, kelli.armbruster@ndsu.edu |