Long-Term Grazing Intensity Research in the Missouri Coteau of North Dakota

Table 3 shows the average daily gain, gain per acre, and body condition scores from the different grazing intensities. Grazing pressure was too light on the heavy and extreme treatments in the first two years of the study, so no significant differences in average daily gains were observed in 1989 and 1990. Since 1990, average daily gain and animal body condition scores have decreased with increasing grazing intensity. The rate at which average daily gain decreases with an increase in stocking rate varies greatly from year to year. The differences between years may be due to variation in forage quality or quantity, the effect of weather on the animals, the animals’ initial weights, or their potential to gain. We would like to begin taking a mid-season weight on the cattle. This will allow us to determine if the animals on the heavily stocked pastures gain consistently less throughout the grazing season or if they gain well in the first half of the grazing season and then lose weight or gain more slowly in the second half of the season. We were able to do this in 2008 but not in 2009. In 2008 all the cattle on all grazing treatments gained at a slower rate in the later part of the grazing season, August 1 to August 25, than they did in the first part of the grazing season, May 20 to August 1. The extreme grazing treatment had a significantly slower rate of gain in the first part of the grazing season than the other treatments, but there was no significant difference in the rate of gain between treatments in the last 25 days of the grazing season.

| Table 3. Average daily gains, gains per acre, and condition scores from different stocking intensities. | ||||||

|

Desired Grazing Intensity |

Average Daily Gains (lbs/head/day) |

|||||

|

2005

|

2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Average 1991-2009 | |

| Light | 0.93a1 | 0.57 | 1.36 | 1.75a | 2.05a | 1.39a |

| Moderate | 0.87a | 0.62 | 1.22 | 1.58ab | 1.99a | 1.28a |

| Heavy | 0.71ab | 0.48 | 1.33 | 1.35b | 1.48b | 1.10b |

| Extreme | 0.39b | 0.13 | 1.16 | 0.95c | 1.09b | 0.79c |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.36 | NS | NS | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.14 |

|

Average Gain (lbs/acre) |

||||||

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Average 1991-2009 | |

| Light | 34.17 | 11.01 | 44.41c | 39.73b | 47.37b | 29.42c |

| Moderate | 63.20 | 20.82 | 69.27bc | 68.61ab | 90.63a | 54.47b |

| Heavy | 65.68 | 20.77 | 107.47ab | 82.15a | 92.72a | 76.03a |

| Extreme | 52.51 | 7.48 | 122.96a | 76.10a | 90.79a | 80.20a |

| LSD (0.05) | NS | NS | 42.67 | 29.04 | 34.31 | 10.64 |

|

Condition Score |

||||||

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | Average 1994-2009 | |

| Light | 5.58a | 5.08 | 5.60 | 6.99a | 5.77 | 5.49a |

|

Moderate

|

5.30a | 5.17 | 5.50 | 6.51b | 5.52 | 5.37ab |

|

Heavy

|

5.27a | 5.02 | 5.54 | 6.38b | 5.46 | 5.24b |

|

Extreme

|

4.83b | 4.81 | 5.41 | 5.82c | 4.97 | 4.92c |

|

LSD (0.05)

|

0.41 | NS | NS | 0.39 | NS | 0.19 |

|

1Means in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at p=0.05.

2Means not significantly different. |

||||||

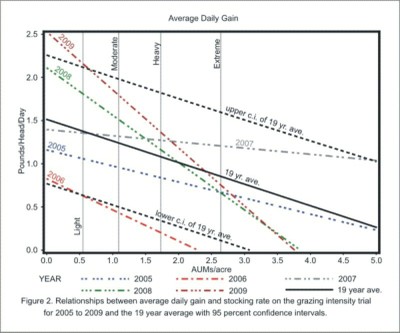

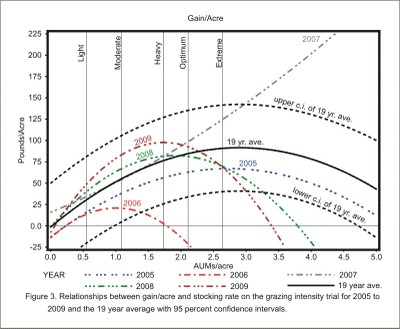

If all years are pooled together, the relationship between rate of gain and stocking rate has an R2 of 0.28, which means that stocking rate explains 28% of the variation in average daily gain between pastures. When only one year is considered at a time, the R2 varies between 0.09 and 0.92, with 0.09 coming from 2007. The next lowest R2 was 2006, with an R2 of 0.25, and third was 2001, with an R2 of 0.45. Therefore, ignoring 2006 and 2007, between 45% and 92% of variation in average daily gain is a result of the difference in stocking rate. Forage production was well above average in 2007 and gains had not become forage-limited on the heavily grazed pastures by the time the cattle were removed (Table 2.). Forage production was well below average in 2006 and cattle were removed early, before the stocking rate had much opportunity to influence average daily gains (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1). The relationships between stocking rate and average daily gain are illustrated in Figure 2. Reference lines indicate the average stocking rates for each of the four grazing treatments. This year average daily gains where greater at low stocking rates than in recent years but they decreased more quickly with increasing stocking rate. Initially, gain/acre increased as the stocking rate increased, but there comes a point when further increases in stocking rates result in reduced gain/acre (see Figure 3). What happens at stocking rates beyond the extreme stocking rate reference line is mainly hypothetical because we have very few observations on which to base our regression lines. However, all but 2001, 2003, and 2007 had at least one observation from a stocking rate higher than the projected rate that would provide maximum gain/acre for the year. Table 4A shows the stocking rate that would have resulted in the maximum gain/acre in each year. Since we cannot predict ahead of time which stocking rate will give the maximum gain/acre in a particular year, it would be impossible to stock each year for maximum gain/acre. In retrospect, if we were to pick one stocking rate that would have resulted in the maximum gain/acre from 1991-2009, it would be 2.11 AUM/acre. This is the point labeled optimum in Figure 3. Table 4B shows what the gain/acre would have been each year if we had stocked at that rate. We predict that if we had stocked at 2.11 AUM/acre each year, gain/acre would have ranged from a loss of 39.3 lbs/acre in 2002 to a gain of 147.3 lbs/acre in 1993 but would have averaged 75.5 lbs/acre. Because so little forage was produced in 2002, the grazing season was cut short and none of the pastures were actually stocked that heavily. The stocking rate on the extreme treatment averaged 1.18 AUM/acre for 2002 and, although gains were not good, only 11 out of the 189 animals in the trial had actually lost weight during the 55 days of grazing. Similarly, in 2006 the grazing season was cut short and the stocking rate on the extreme treatment averaged 1.55 AUM/acre. However, in that year, 46 of the 191 animals in the trial had lost weight before they were removed at the end of the 77-day grazing season. Table 4C shows what the gain/acre would have been each year if the stocking rate had been held constant at 1.09 AUM/acre, the average of the moderate treatment over this period.

| Table 4. Comparison of gain in lbs. per acre from selected stocking rates. | ||||||

|

A |

B |

C |

||||

| Stocking rate that would result in the maximum gain/acre in each year |

Stocking rate that if held constant would result in the maximum gain/acre over the 19-year period. |

Gain/acre over the 19-year period if stocking rate where held constant at 1.09 AUMs/acre, the average of the moderate treatment over this period. |

||||

| Year | AUMs/acre | gain/acre | AUMs/acre | gain/acre | AUMs/acre | gain/acre |

| 1991 | 2.26 | 62.5 | 2.11 | 62.2 | 1.09 | 45.4 |

| 1992 | 2.68 | 134.8 | 2.11 | 128.4 | 1.09 | 86.1 |

| 1993 | 3.41 | 175.8 | 2.11 | 147.3 | 1.09 | 85.6 |

| 1994 | 2.27 | 58.1 | 2.11 | 57.8 | 1.09 | 42.1 |

| 1995 | 3.08 | 84.7 | 2.11 | 75.8 | 1.09 | 47.6 |

| 1996 | 2.04 | 57.0 | 2.11 | 56.9 | 1.09 | 43.1 |

| 1997 | 1.92 | 92.4 | 2.11 | 91.4 | 1.09 | 72.5 |

| 1998 | 2.08 | 91.2 | 2.11 | 91.2 | 1.09 | 67.1 |

| 1999 | 3.18 | 111.4 | 2.11 | 97.5 | 1.09 | 58.7 |

| 2000 | 2.81 | 76.6 | 2.11 | 71.7 | 1.09 | 47.4 |

| 2001 | * | 2.11 | 98.5 | 1.09 | 56.8 | |

| 2002 | 0.94 | 41.5 | 2.11 | -39.3 | 1.09 | 40.1 |

| 2003 | * | 2.11 | 68.3 | 1.09 | 43.3 | |

| 2004 | 2.23 | 112.6 | 2.11 | 112.2 | 1.09 | 76.9 |

| 2005 | 2.73 | 67.0 | 2.11 | 62.8 | 1.09 | 38.1 |

| 2006 | 1.01 | 20.8 | 2.11 | -21.0 | 20.6 | |

| 2007 | * | 2.11 | 98.3 | 1.09 | 54.3 | |

| 2008 | 1.90 | 82.2 | 2.11 | 81.3 | 1.09 | 67.0 |

| 2009 | 1.73 | 97.7 | 2.11 | 92.7 | 1.09 | 83.3 |

| 19-year avg. | 2.27 | 85.4 | 2.11 | 75.5 | 1.09 | 56.6 |

| * The regressions for 2001, 2003 and 2007 were not suitable to project the peak in gain/acre. | ||||||

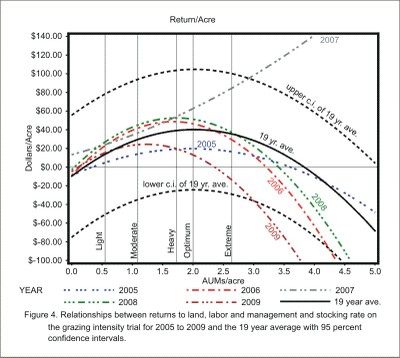

Figure 4 shows the relationship between stocking rate and economic return. Costs for land, labor, and management are not included because these values vary greatly from one operation to another. If cattle prices were constant, then return/acre would peak at a stocking rate somewhere below maximum gain/acre, with the exact point depending on carrying costs (interest, death loss, salt and mineral cost, veterinary cost, transportation, labor, and land). However, when cattle are worth more per hundredweight in the spring than they are in the fall, the point of maximum return/acre occurs at a lower stocking rate. When the cattle are worth more in the fall, the maximum return/acre occurs at a higher stocking rate. Again, returns for stocking rates beyond the extreme stocking rate reference line are hypothetical and again all but 2001, 2003, and 2007 had at least one observation from a stocking rate higher than the rate that would provide maximum return to land, labor, and management for the year. Table 5 shows what the optimum return/acre would have been for each year if stocking rate were set for the optimum for that year (A), if the stocking rate were held at a constant optimum rate (B), or if held the stocking rate were held constant at the moderate stocking rate (C). The peaks of the curves in Figure 4 correspond to these optimum stocking rates. If we were to pick one constant stocking rate that would have provided the maximum return/acre over the last 19-years, it would be 2.00 AUM/acre. This is the point labeled "optimum" in Figure 4. This year cattle prices where higher in the spring than in the fall for cattle weighing less than 850 pounds. This coupled with the lower rate of gain of cattle on the higher stocking rates would put the maximum return for 2009 at $24.41/acre if stocked at 1.23 AUM/acre. Although the average return/acre is higher under the optimum stocking rate, there were five years with negative returns, while only one year had a negative return under the moderate stocking rate. (Costs for land, labor, and management have not been subtracted). Comparing Tables 4 and 5 shows that in all but five years (1992, 1996, 1999, 2004, and 2006) the stocking rate with the greatest economic return was less than the rate with the greatest gain per acre.

| Table 5. Comparison of return to land, labor and management from selected stocking rates. | |||||||||

|

A |

B |

C |

|||||||

| Stocking rate that would result in the maximum return/acre to land, labor and management in each year. |

Stocking rate that if held constant would result in the maximum return to land, labor and management over the 19-year period. |

Returns/acre to land, labor and management over the 19-year period if stocking rate were held constant at 1.09 AUMs/acre the average of the moderate treatment over this period. |

|||||||

| Year | AUMs/acre | returns/acre | gain/acre | AUMs/acre | returns/acre | gain/acre | AUMs/acre | returns/acre | gain/acre |

| 1991 | 0.88 | $4.10 | 38.8 | 2.00 | ($5.14) | 61.7 | 1.09 | $3.77 | 45.4 |

| 1992 | 3.12 | $97.11 | 130.9 | 2.00 | $84.03 | 125.8 | 1.09 | $54.44 | 86.1 |

| 1993 | 2.39 | $105.11 | 158.3 | 2.00 | $102.26 | 142.4 | 1.09 | $73.27 | 85.6 |

| 1994 | 0.67 | $1.99 | 28.5 | 2.00 | ($8.05) | 57.3 | 1.09 | $0.98 | 42.1 |

| 1995 | 1.44 | $2.05 | 59.5 | 2.00 | ($0.07) | 73.8 | 1.09 | $1.23 | 47.6 |

| 1996 | 2.06 | $31.83 | 56.9 | 2.00 | $31.80 | 56.9 | 1.09 | $23.92 | 43.1 |

| 1997 | 1.11 | $13.35 | 73.5 | 2.00 | $3.90 | 92.2 | 1.09 | $13.34 | 72.5 |

| 1998 | 1.01 | $2.11 | 63.1 | 2.00 | ($7.61) | 91.1 | 1.09 | $2.05 | 67.1 |

| 1999 | 3.24 | $56.58 | 111.3 | 2.00 | $47.36 | 94.5 | 1.09 | $28.93 | 58.7 |

| 2000 | 2.19 | $18.05 | 72.8 | 2.00 | $17.89 | 70.1 | 1.09 | $12.61 | 47.4 |

| 2001 | * | 2.00 | $46.82 | 94.4 | 1.09 | $28.35 | 56.8 | ||

| 2002 | 0.31 | ($1.49) | 17.8 | 2.00 | ($39.58) | -25.2 | 1.09 | ($9.68) | 40.1 |

| 2003 | * | 2.00 | $88.76 | 65.4 | 1.09 | $53.26 | 43.3 | ||

| 2004 | 3.04 | $121.71 | 94.8 | 2.00 | $106.00 | 111.2 | 1.09 | $66.58 | 76.9 |

| 2005 | 1.97 | $19.76 | 60.8 | 2.00 | $19.76 | 61.3 | 1.09 | $14.01 | 38.1 |

| 2006 | 1.67 | $48.66 | 5.6 | 2.00 | $46.43 | -13.3 | 1.09 | $41.76 | 20.6 |

| 2007 | * | 2.00 | $62.59 | 93.3 | 1.09 | $36.59 | 54.3 | ||

| 2008 | 1.73 | $52.63 | 81.5 | 2.00 | $51.26 | 82.0 | 1.09 | $45.09 | 67.0 |

| 2009 | 1.23 | $24.41 | 89.0 | 2.00 | $13.06 | 95.1 | 1.09 | $24.02 | 83.3 |

| 19-year avg. | 1.75 | $37.31 | 71.4 | 2.00 | $34.81 | 75.3 | 1.09 | $27.08 | 56.6 |

| * The regressions for 2001, 2003 and 2007 were not suitable to project the peak in returns to land, labor and management. | |||||||||

Next section: Forage Production and Utilization