Sunflower Meal in Beef Cattle Diets (AS1623, Reviewed Sept. 2017)

Availability: Web only

Photo courtesy of National Sunflower Association

Sunflowers were first domesticated by Native Americans in the southwestern United States in about 3000 BC. The crop was transported to Europe by Spanish explorers in approximately 1500 AD and the first patent for extracting oil from sunflower was issued in England in 1716. Commercial development as a field crop occurred during the past half century. Sunflower oil is a major edible oil for humans worldwide. Oil sunflowers dominate U.S. production, accounting for more than 80 percent of the domestic crop.

Sunflower Meal

Sunflower meal is the third largest source of protein supplement used for livestock behind soybean and rapeseed (canola) meals (U.S. Department of Agriculture – Foreign Agriculture Service, 2017).

Sunflower meal is the residual product when the oil fraction is removed from the black oil seeds by “crushing,” or more specifically, prepress solvent extraction. The supply of sunflower meal in the U.S. varies by year according to acres and yield of sunflowers harvested, with some seasonal variation in output.

Sunflowers are processed year round with most sunflowers processed from October through March. Oil sunflowers generally are grown in the Great Plains region of the U.S., from Texas to North Dakota.

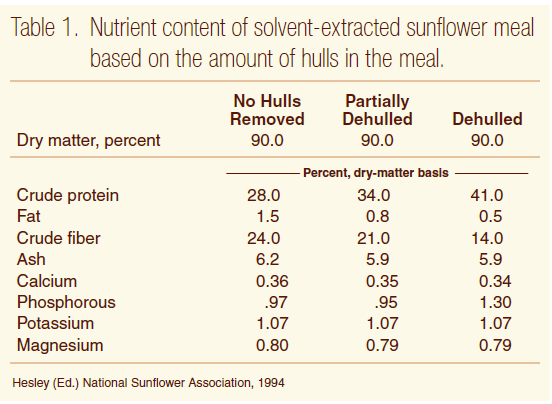

Nutrients in sunflower meal can vary depending on several factors. The amount and composition of meal is affected by oil content of the seed, extent of hull removal prior to crushing and the efficiency of oil extraction (Hesley, 1994).

The proportion of the hull removed before processing differs among crushing plants. In some cases, a portion of the hulls may be added back to the meal after crushing or burned for heat. The amount of hull or fiber in the meal is the major source of variation in nutrients (Table 1).

Prepress solvent extraction of whole seeds with no dehulling produces meal with a crude protein content of 25 to 28 percent, partial dehulling yields 34 to 38 percent crude protein and completely dehulled sunflower meal commonly yields 40 percent or more crude protein. Testing of sunflower meal is advised because the protein levels are often higher than the minimum listed on the feed tag.

Sunflower meal is marketed and shipped in meal form or as pellets. Bulk density is greater with pelleted meal, reducing transportation costs.

Sunflower meal without hulls that is 40 percent crude protein is approximately 32 pounds per cubic foot, with higher-fiber/lower-protein meals slightly less (Lusas, 1991). Sunflower meal is dry and can be stored for extended periods of time without significant loss or degradation (Hesley, 1994).

Protein in Sunflower Meal

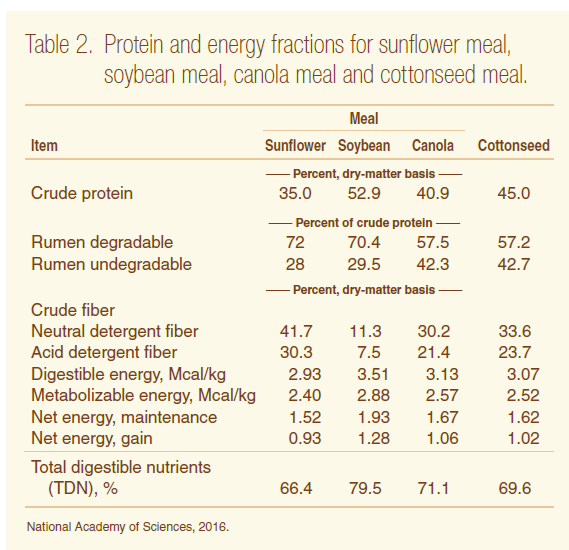

Sunflower meal is lower in crude protein that other oilseed meals such as soybean, canola or cottonseed (Table 2, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine [NAS], 2016). The crude protein level can vary based on the amount of hull present in the meal. Some processors will add back more hull, while others have markets for the hull (bedding, compost, etc.).

The more hulls present, the lower the crude protein in the meal. Dehulled meal can have as much as 41 percent crude protein (Table 1), while meals with greater hull levels may be as low as 28 percent crude protein. Prices for sunflower meal are based on protein content in relation to other locally available oilseed meals.

Sunflower meal is highly rumen degradable, with 72 percent available to microbes in the rumen. Sunflower meal is more ruminally degradable than soybean meal (70 percent) or canola meal (58 percent) (NAS, 2016) (Table 2).

Rumen-degradable protein is required for a healthy microbial population, which is necessary for thorough digestion of forage and fiber, making this protein source useful to all beef cattle and other ruminants.

Heat treatment or toasting of meal from the solvent-extraction process may increase the proportion of undegradable protein, but little information is available on the effects of temperature and time on sunflower meal.

Energy in Sunflower Meal

Energy values of sunflower meal are lower than canola, soybean or cottonseed meal (NAS, 2016) (Table 2). Energy varies substantially with the fiber level and residual oil content. Higher levels of hulls included in the final meal product lower the energy content and reduce bulk density.

The mechanical process of oil extraction leaves more residual oil in the meal, often 5 to 10 percent, depending on the efficiency of the extraction process. Elevated oil content in mechanically extracted meals provides greater energy density, which may be more valuable for animals with higher nutrient requirements or where limited amounts of supplement are fed. Prepress solvent extraction reduces residual oil to 1.5 percent or less (Hesley, 1994).

Sunflower Meal in Feeder Calf Diets

Sunflower meal can be used as the sole source of protein in beef rations (Richardson and Anderson, 1981). In trials comparing sunflower meal with other protein sources, equal animal performance commonly is observed based on isonitrogenous diets from different sources.

Dinusson et al. (1980) fed growing heifers a forage-based diet supplemented with dehulled sunflower meal (43 percent crude protein) or soybean meal. Heifers fed dehulled sunflower meal gained 1.81 pounds per day, compared with 1.83 pounds per day for heifers fed soybean meal. Gain per unit feed was .077 for both treatments.

Landblom et al. (1987) compared sunflower meal (34 percent crude protein) to soybean meal and barley distillers grains in growing heifer diets. Average daily gains were 2.40, 2.47 and 2.47 pounds, respectively, for sunflower meal, soybean meal and barley distillers grains.

Feed efficiency favored barley distillers grains at 14.3 pounds of feed per pound of gain, with soybean meal at 14.9 and sunflower meal at 15.2. In this trial, feed cost per unit gain was equal for sunflower and soybean meals due to a lower price per unit of protein for sunflower meal.

Richardson et al. (1981) substituted sunflower meal for cottonseed meal in growing and finishing diets for steers at 0, 5.5, 11 and 22 percent of diet dry matter (DM). They reported equal total diet digestion for steer calves fed cottonseed meal and sunflower meal when fed at isonitrogenous and equal fiber levels up to 11 percent sunflower meal.

Digestibility of dietary dry matter and organic matter was highest (P < .05) for the 22 percent sunflower meal treatment. The same authors also reported equal digestibility of high-forage diets for steer calves when sunflower meal was substituted for urea as a nitrogen source and fed at 0, 5, 10 and 20 percent of diet dry matter.

Patterson et al. (1999a) fed 33.5 percent crude protein sunflower meal to provide .20 or .40 pound per day of protein, compared with .40 pound of protein from canola meal, edible beans or a mixture of edible beans and sunflower meal. In this trial, medium-quality forage (8.3 percent crude protein) was fed to steer calves in confinement to determine in situ digestion kinetics.

No differences (P > .10) were observed due to supplement treatment in degradation of dry matter, neutral detergent fiber or acid detergent fiber in the forage. However, differences were observed in the digestibility of the protein supplements, with edible beans (P = .02) and canola meal (P = .13) more digestible than sunflower meal.

Jordan et al. (1998) compared soybean meal with a sunflower meal (81.2 percent of protein supplement, dry-matter basis) and feather meal (11.2 percent of protein supplement) mixture for calves grazing cornstalks. Feather meal provided a source of rumen-undegradable protein, with the degradable protein provided by sunflower meal.

Gains were equal (P > .05) during the two-year trial. Economic comparison strongly favored the feather meal-sunflower meal combination, with a cost savings of 5 cents per head per day in 1998.

Sunflower meal was compared with soybean meal and a sunflower-soybean meal mixture in isonitrogenous supplements in corn-based finishing diets that also contained 1 percent urea. The urea and sunflower meal provided adequate ruminal-degradable nitrogen, with the undegradable nitrogen provide by the corn (Milton et al., 1997). No differences were detected for gain (3.53 pounds per day, P=.18), feed efficiency (6.80, P=.85) or carcass traits (P=.64) due to treatment.

Sunflower Meal in Cow Diets

Cows consuming low-quality forages such as winter range, crop aftermath or other low-quality forages can utilize supplemental degradable protein to increase total intake, forage digestibility and performance (Kartchner, 1980; Gray, 1995). Protein can be supplemented with a number of different feeds, coproducts or oilseed meals. Least-cost sources are critical to profitability, and sunflower meal is often very price-competitive per unit of crude protein.

Sunflower meal has been used widely in beef cow supplementation programs. Gray (1995) reported that sunflower meal will minimize weight and condition score losses for beef cows. Ilse et al. (2007) reported equal performance in heifers and lactating cows when sunflower meal was compared with linseed meal in isonitrogenous supplements.

Patterson et al. (1999b) fed cows grazing winter range protein supplement from 1) edible beans (navy, pinto, black, etc.), 2) sunflower meal, 3) a mix of edible beans and sunflower meal, 4) canola meal all at .38 pound per day of crude protein or 5) sunflower meal at .20 pound of protein per day. Cows fed sunflower meal at .20 pound of protein lost more weight during gestation (P < .05), but no other differences were detected, suggesting supplemental protein levels of .38 pound may have been higher than requirements.

No differences were observed in weaning weight or pregnancy rate (P >.05). Dry or edible beans fed alone resulted in some palatability problems; however, mixing edible beans and sunflower meal eliminated the problem.

Jordan et al. (1997) compared protein supplements with equal amounts of metabolizable protein and rumen-undegradable protein from soybean meal or a feather meal-sunflower meal combination. Supplements were fed to cows grazing cornstalks at 1.5 pounds per day as fed. The combination supplement was 81.2 percent (DM basis) sunflower meal and 11.2 percent feather meal.

Cows and heifers gained the same (P > .15) on the two treatments. Protein costs were 4 cents per head per day lower for the feather meal-sunflower meal supplement.

Lactating mature beef cows were fed three different protein supplements: 4.55 pounds of sunflower meal (38.1 percent crude protein), 5 pounds of lupines (33.2 percent crude protein) or 10 pounds of wheat screenings (16.6 percent crude protein) in straw-based diets. No differences (P > .05) were observed for weight change, cow condition score or reproduction due to supplement treatment (Anderson, 1993). Calf gains were 2.11 pounds daily for sunflower meal, compared with 2 for wheat screenings and 2.01 for lupines (P > .05).

Sunflower meal was used as 57 percent of a formulated protein supplement (1.80 pounds per head per day), contributing degradable protein to lactating cow diets (Anderson et. al., 2000).

Feeding Whole Sunflower Seeds or Screenings

Whole sunflower seed can be fed to most ruminants as a protein and energy (from fat) source. Cracking or rolling sunflower seeds prior to feeding does not appear to be advantageous. The size of the seed results in cows chewing and breaking down the product during digestion (Ahrar and Schingoethe, 1978). Feeding sunflower seeds in a mixed ration eliminates any issues of feed preference or palatability.

Whole sunflower seeds contain up to 42 percent fat on a DM basis. Too much fat in ruminant diets will decrease forage digestibility. Fat should not exceed 6 percent of the diet dry matter, so as a rule of thumb, limit sunflower seeds to no more than 5 pounds per head for mature cows and 3 pounds for growing calves.

Sunflower seeds or screenings from drought- or frost-damaged crops may be lower in oil content. Light test weight seed from an early frost or insect damage still can be used for feed. Screenings should be tested periodically for nutrient content because the feed quality of screenings can decrease significantly during the season (Anderson, 2002).

Sclerotia bodies from sclerotinia-infected sunflowers have not caused feeding or performance problems with beef cows (Anderson and Bock, 2000) when fed as 52 percent of the sunflower screenings by weight.

Sclerotia produced in a sclerotinia-infected sunflower.

(Photo by S. Markell, NDSU)

Close-up of sclerotia bodies found in sunflower screenings.

(Photo by M. Wunsch, NDSU)

Summary

Sunflower meal is preferred in lower-quality forage rations, when cattle are grazing winter range or in crop residue such as corn stover. Sunflower meal also is useful in high-forage growing rations for steers and developing heifers, or in high-corn grain finishing rations. The relatively high fiber of sunflower meal should be considered when pricing sunflower meal. However, it makes an excellent source of rumen-degradable protein for beef cattle.

Literature Cited

Ahrar, M., and D.J. Schingoethe. 1978. The feeding value of regular and heat-treated soybean meal and sunflower meal for dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 61 (Suppl. 1):168 (abstr.).

Anderson, V.L. 2002. Sunflower screenings, barley malt, or wheat midds in lactating beef cow diets. NDSU Carrington Research Extension Center Beef Production Field Day Report. Vol. 25:33-36.

Anderson, V.L., J.S. Caton, J.D. Kirsch and D.A. Redmer. 2000. Effect of crambe meal on performance, reproduction, and thyroid hormone levels in gestating and lactating beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 78:2269-2274.

Anderson, V.L., and E. Bock. 2000. Sclerotinia-infected sunflowers as a feed source for pregnant and non-pregnant mature beef cows. NDSU Carrington Research Extension Center Beef Production Field Day Report. Vol. 23:14-15.

Anderson, V.L. 1993. Low input drylot beef cow/calf production with alternative crop products. In: Ruminant production systems inter-related with non-traditional crop management. Final report to NC Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. N.D. Ag. Exp. Station. Carrington Research Extension Center pp 16-23.

Dinusson, W.E., L.J. Johnson and R.B. Danielson. 1981. Protein sources for growing beef heifers. Annual Report. p 10-11. Dept. of Anim. Sci. North Dakota State University, Fargo.

Gray, K.S. 1995. Effects of sunflower meal and whole sunflower seed on winter grazing performance and on intake, digestibility and dry matter disappearance of low-quality forage in beef cows. M.S. thesis. Colorado State Univ., Fort Collins.

Hesley, J. (Ed). 1994. Sunflower meal use in livestock rations. National Sunflower Association, Bismarck, N.D.

Jordan, D.J., Terry Klopfenstein and Mark Klemesrud. 1997. Evaluation of feather meal for calves grazing cornstalks. Nebraska Beef Report, pp 13-14.

Jordan, D.J., Terry Klopfenstein, Mark Klemesrud and Drew Shain. 1998. Evaluation of feather meal for cows grazing cornstalks. Nebraska Beef Report, pp. 40-42.

Kartchner, R.J. 1980. Effects of protein and energy supplementation of cows grazing native winter range forage on intake and

digestibility. J. Anim. Sci. 51:432-438.

Landblom, D.G., J.L. Nelson, L. Johnson and W.D. Slanger. 1987. A comparison of barley distillers dried grain, sunflower meal and soybean oil meal as protein supplements in backgrounding rations. N.D. cow/calf conference proceedings. pp. 22-26.

Lusas, E.W. 1991. Sunflower meals and food proteins. pp. 26-29. In Sunflower Handbook, National Sunflower Assn. Bismarck, N.D.

Milton, C.T., R.T. Brandt Jr., E.C. Titgemeyer and G.L. Kuhl. 1997. Effect of degradable and escape protein and roughage type on performance and carcass characteristics of finishing yearling steers. J. Anim. Sci. 75:2834-2840.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. 2016. Eighth Revised Edition. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C.

Patterson, H.H., J.C. Whittier and L.R. Rittenhouse. 1999a. Effects of cull beans, sunflower meal, and canola meal as protein supplement to beef steers consuming grass hay on in situ digestion kinetics. The Prof. Anim. Scientist 15:185-190.

Patterson, H.H., J.C. Whittier, L.R. Rittenhous and D.N. Schutz. 1999b. Performance of beef cows receiving cull beans, sunflower meal, and canola meal as protein supplement while grazing native winter range in eastern Colorado. J. Anim. Sci. 77:750-755.

Richardson, C.R., and G.D. Anderson. 1981. Sunflowers: beef applications. Feed Management. 32(6):30.

Richardson, C.R., R.N. Beville, R.K. Ratcliff and R.C. Albin. 1981. Sunflower meal as a protein supplement for growing ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 53:5577-560.

USDA-FAS. Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. Accessed Aug. 24, 2017.

This publication was authored by Vern Anderson, former animal scientist at NDSU’s Carrington Research Extension Center, and Greg Lardy, head of the NDSU Animal Sciences Department, 2012.