Ranchers Guide to Grassland Management IV (R1707, Oct. 2014)

Availability: Web only

Introduction

This guide is intended to serve as a quick reference for ranchers looking for information on grazing management. As such, it does not attempt to cover any single topic in great depth. Instead, it provides general information on a variety of subjects related to range, pasture and hay land management. References for other sources of information are provided should the reader wish to research the topic in greater depth.

The basic outline for this handbook was developed by a small group of ranchers consisting of Larry Woodbury, Keith Bartholomay, Darell Evanson and Lynn Wolf. They provided the authors with ideas and guidelines in producing a user-friendly guide containing topical information they felt their fellow ranchers would find useful. The authors thank Stan Boltz, Miranda Meehan, Mark Hayek, Don Kirby, Jay Mar, Merlyn Lepp, Darell Evanson, David Lautt, Gary Moran, Myron Senechal, Keith Bartholomay, and Todd Hagel for review and constructive criticism.

The authors also would thank Miranda Meehan and Craig Brumbaugh for their assistance in writing the Riparian Grazing Management section.

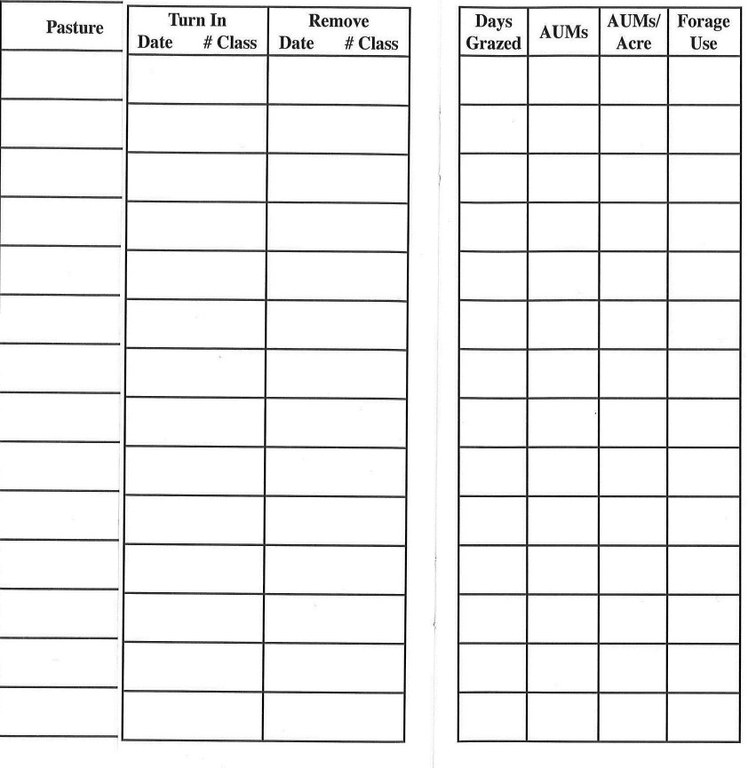

Recordkeeping

Keeping accurate records on how many livestock are in a pasture or pastures, how long they are in a pasture or pastures, growing conditions and some general notes on pasture condition is part of a monitoring system. This information is valuable in analyzing changes that may occur due to grazing patterns and environmental conditions.

This can be as simple as a pocket notebook or as complex as a detailed recordkeeping program. This document contains a range and pasture recordkeeping system for your use. It allows you to document pasture turn-in dates, rotation dates, livestock numbers and weather. When record keeping notes and observations are combined with monitoring data/information, a more informed decision is possible.

Definitions

Understanding the terminology in rangeland management is important when interpreting ideas, strategies and goals. The following are common terms adapted from the Society for Range Management in the “Glossary of Terms Used in Range Management (1989)”:

Acclimatized species: An introduced species that has become adapted to a new climate or a different environment and can perpetuate itself in the community without cultural treatment (cf. exotic, introduced species)

Aerial photograph: A photograph of the Earth’s surface taken from airborne equipment, sometimes called aerial photo or air-photograph

Aftermath: Residue and/or regrowth of plants grazed after harvesting of a crop

Allelopathy: Chemical inhibition of one organism by another

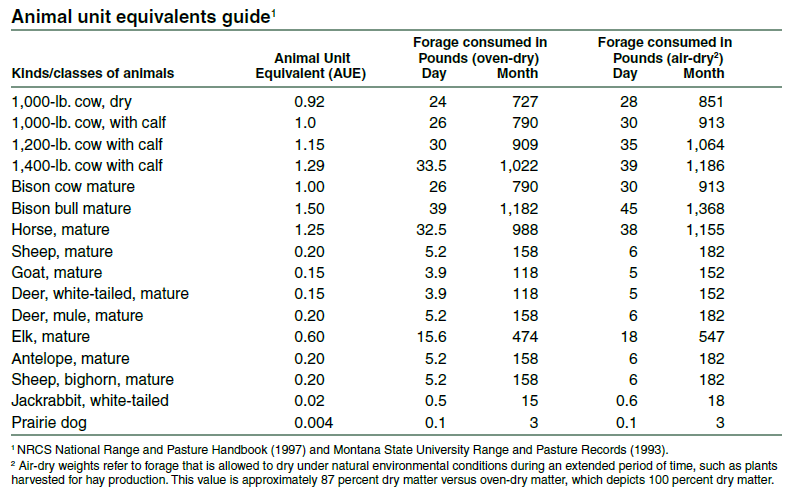

Animal unit: Considered to be one mature cow of approximately 1,000 pounds, dry or with calf up to 6 months of age, or their equivalent, based on a standardized amount of forage consumed (Abbr = AU)

Animal unit day: The amount of forage on a dry-matter basis required by one animal unit in one day based on a 26 pounds forage allowance based on oven dried or 30 pounds forage allowance based on air dried (Abbr = AUD)

Animal unit equivalent: A number expressing the energy requirements of a particular kind or class of animal relative to one animal unit (Abbr = AUE)

Animal unit month: The amount of dry forage required by one animal unit for one month based on a forage allowance of 26 pounds per day oven dried or 30 pounds per day air dried (Abbr = AUM)

Animal unit conversion factor: A numerical figure expressing the forage requirements of a particular kind or class of animal related to the requirement for an animal unit. A conversion factor is satisfactory with respect to the amount of forage required to maintain an animal, but it may not be applicable in determining stocking rates for range use for particular kinds or classes of animals because of different grazing preferences

Annual plant: A plant that completes its life cycle and dies in one year or less

Apical dominance: Domination and control of meristematic leaves or buds on the lower stem, roots or rhizomes by hormones produced by apical meristems on the tips and upper branches of plants, particularly woody plants

Auxin: A plant hormone promoting or regulating growth

Backfiring: Ignition of a fire on the leeward (downwind) side of a burn area resulting in a slow-moving ground fire (cf. headfiring)

Badland: A land type consisting of steep or very steep barren land usually broken by an intricate maze of narrow ravines, sharp crests and pinnacles resulting from serious erosion of soft geologic materials; most common in and or semiarid regions; a miscellaneous land type

Bentonite: A natural clay deposit that has high swelling capabilities when saturated; used to seal earthen stock ponds

Biennial: A plant that lives for two years, producing vegetative growth the first year and usually

blooming and fruiting in the second year and then dying

Biomass: The total amount of living plants and animals above and below ground in an area at a given time

Biome: A major biotic site consisting of plant and animal communities having similarities in form and environmental conditions but not including the abiotic portion of the environment

Biota: All the species of plants and animals occurring in an area or region

Biotic: Refers to living components of an ecosystem; for example, plants and animals

Blowout: (1) An excavation in areas of loose soil, usually sand, produced by wind; (2) a breakthrough or rupture of a soil surface attributable to hydraulic pressure, usually associated with sand soils

Breeding herd: The animals retained for breeding purposes to provide for the perpetuation of the herd or band; excludes animals being prepared for market

Broadcast seeding: Process of scattering seed on the surface of the soil prior to natural or artificial means of covering the seed with soil (cf. dill seeding)

Browse: (n.) That part of leaf and twig growth of shrubs, woody vines and trees available for animal consumption; (v.) act of consuming browse (cf. graze)

Brush: A term encompassing various species of shrubs or small trees usually considered undesirable for livestock or timber management. The same species may have value for browse, wildlife habitat or watershed protection.

Brush control: Reduction of unwanted woody plants through fire, chemicals, mechanical methods or biological means to achieve desired land management goals

Brush management: Manipulating woody plant cover to obtain desired quantities and types of woody cover and/or to reduce competition with herbaceous understory vegetation in accordance with ecologically sound resource management objectives

Buck-fence: A fence constructed of wooden poles fastened horizontally to wooden cross-members; also called buck-pole fence. Such fences withstand heavy snows in mountainous regions and eliminate the need for digging holes for posts in rocky terrain.

Bunch grass: A grass having the characteristic growth habit of forming a bunch; lacks stolons or rhizomes (cf. sod grass)

Burn: An area over which fire has passed recently

Butte: An isolated hill with relatively steep sides (cf. mesa)

C-3 plant: A plant employing the pentose phosphate pathway of carbon dioxide assimilation during photosynthesis; often a cool-season plant

C-4 plant: A plant employing the dicarboxylic acid pathway of carbon dioxide assimilation during photosynthesis; often a warm-season plant

Cactus: A spiny, succulent plant of the Cactaceae family

Canopy: (1) The vertical projection downward of the aerial portion of vegetation, usually expressed as a percent of the ground so occupied; (2) the aerial portion of the overstory vegetation (cf. canopy cover)

Canopy cover: The percentage of ground covered by a vertical projection of the outermost perimeter of the natural spread of foliage of plants. Small openings within the canopy are included. It may exceed 100 percent. (Syn. aerial cover)

Carrying capacity: The maximum stocking rate possible that is consistent with maintaining or improving vegetation or related resources. It may vary from year to year on the same area due to fluctuating forage production. (cf. grazing capacity)

Cell: A grazing arrangement comprised of numerous subdivisions (paddocks or pastures) often formed by electrical fencing, with a central component to facilitate livestock management and movement to the various subdivisions; normally used to facilitate a form of controlled grazing (cf. paddock)

Class of animal: Description of age and/or sex group for a particular kind of animal; for example, cow, calf, yearling, ewe, doe, fawn

Claypan: A dense, compact layer in the subsoil having much higher clay content than the overlaying material from which it is separated by a sharply designed boundary; formed by downward movement of clay or by synthetic of clay in place during soil formation. Claypans are usually hard when dry and plastic and sticky when wet. They usually impede the movement of water and air. (cf. hardpan)

Climax: (1) The final or stable biotic community in a successional series that is self-perpetuating and in dynamic equilibrium with the physical habitat; (2) the assumed end point in succession (cf. potential natural community)

Community (plant community): An assemblage of plants occurring together at any point in time, while denoting no particular ecological status; a unit of vegetation

Companion crop: A crop sown with another crop (perennial forage or trees or shrubs) that is allowed to mature and provide a return in the first year (cf. nurse crop)

Complementary pasture: Short-term forage crop (not necessarily annual) planted for use by domestic stock to enhance the management and productivity of the ranch

Concentrate feed: Grains or their products and other processed food materials that contain a high proportion of nutrients and are low in fiber and water

Conservation: The use and management of natural resources according to principles that assure their sustained economic and/or social benefits without impairment of environmental quality

Conservation district: A public organization created under a state’s enabling law as a special-purpose district to develop and carry out a program of soil, water and related resource conservation, use and development within its boundaries; usually a subdivision of state government with a local governing body and always with limited authorities; often called a soil conservation district or a soil and water conservation district

Conservation plan: The recorded decisions of a landowner or operator cooperating with your local conservation district on how he/she plans, within practical limits, to use his/her land according to its capability and to treat it according to its needs for maintenance or improvement of the soil, water and plant resources

Consumption: Dietary intake based on (1) amounts of specific forages and other feedstuffs or (2) amounts of specific nutrients

Contact herbicide: A herbicide that kills primarily by contact with plant tissue rather than as a result of translocation

Continuous grazing: The grazing of a specific unit by livestock throughout a year or for that part of the year during which grazing is feasible. The term is not necessarily synonymous with year-long grazing because seasonal grazing may be involved.

Cool-season plant: A plant that generally makes the major portion of its growth during the late fall, winter and early spring. Cool-season species generally exhibit the C-3 photosynthetic pathway.

Coordinated resource management planning: The process whereby various user groups are involved in discussion of alternate resource uses and collectively diagnose management problems, establish goals and objectives, and evaluate multiple use resource management

Coulee: The term used for deep gulch or ravine in the northern U.S.

Cover: (1) The plants or plant parts, living or dead, on the surface of the ground. Vegetative cover or herbage cover is composed of living plants and litter cover of dead parts of plants (Syn. foliar cover). (2) The area of ground cover by plants of one or more species (cf. basal area)

Cover type: The existing vegetation of an area

Creep feeding: Supplemental feeding of suckling livestock in such a manner that the feed is not available to the mothers or other mature livestock

Cryptogam: A plant in any of the groups Thallophytes, Byophyte and Pteridiophytes; mosses, lichens and ferns

Cultivar: A named variety selected within a plant species distinguished by any morphological, physiological, cytological or chemical characteristics; a variety of plant produced and maintained by cultivation that genetically is retained through subsequent generations

Cured forage: Forage, standing or harvested, that has been dried and preserved naturally or artificially for future use (cf. stockpiling)

Debris: Accumulated plant and animal remains

Deciduous (plant): Plant parts, particularly leaves that are shed at regular intervals or at a given stage of development. A deciduous plant regularly loses or sheds its leaves. (cf. evergreen)

Decomposer: Heterotrophic organisms, chiefly the microorganisms, that break down the bodies of dead animals or parts of dead plants and absorb some of the decomposition products while releasing similar compounds usable by producers

Decreaser: Plant species of the original or climax vegetation that will decrease in relative amount with continued disturbance to the norm; for example, heavy defoliation, fire drought. Some agencies use this only in relation to response to overgrazing.

Deferment: Delay of livestock grazing in an area for an adequate period of time to provide for plant reproduction, establishment of new plants or restoration of vigor of existing plants (cf. deferred grazing, rest)

Deferred grazing: The use of deferment in grazing management of a management unit but not in a systematic rotation including other units (cf. grazing system)

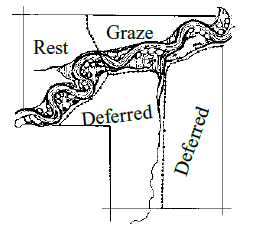

Deferred rotation: Any grazing system that provides for a systematic rotation of the deferment among pastures

Defoliation: The removal of plant leaves by grazing or browsing, cutting, chemical defoliant or natural phenomena such as hail, fire or frost

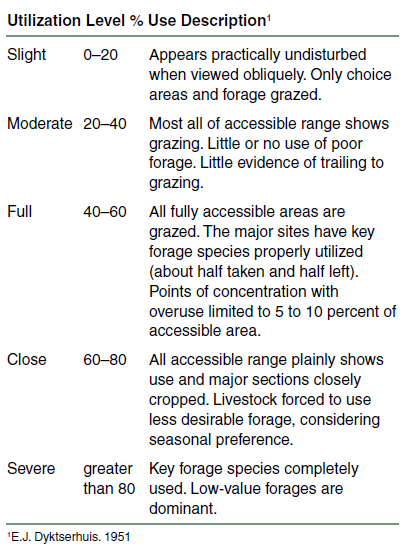

Degree of use: The proportion of current year’s forage production that is consumed and/or destroyed by grazing animals; may refer to a single species or the vegetation as a whole (Syn. Use)

Density: The number of individuals per unit area. It is not a measure of cover. However, in the past, the term “density” has been used to mean cover. (cf. frequency)

Desert: An arid area with insufficient available water for dense plant growth

Desirable plant species: Species that contribute positively to the management objectives

Desired plant community: A plant community that produces the kind, proportion and amount of vegetation necessary for meeting or exceeding the land use plan/activity plan objectives established for an ecological site or sites. The desired plant community must be consistent with the site’s capability to produce the desired vegetation through management, land treatment or a combination of the two.

Deteriorated range: Range in which vegetation and soils departed significantly from the natural potential. Corrective management measures such as seeding would change the designation from deteriorated range to some other term. (Syn. degenerated range)

Detritus: Fragmented particulate organic matter derived from the decomposition of debris

Diurnal: Active during daylight hours

Diversity: The distribution and abundance of different plants and animal communities in an area

Dominant: (1) Plant species or species groups, which by means of their number, coverage or site, have considerable influence or control upon the conditions of existence of associated species; (2) those individual animals that, by their aggressive behavior or otherwise, determine the behavior of one or more animals resulting in the establishment of a social hierarchy

Draw: A natural watercourse, including the channel and adjacent areas on either side, that occasionally may overflow or receive extra water from higher adjacent areas; generally having intermittent flows associated with higher intensity rainfall

Drill seeding: Planting seed directly into the soil with a drill in rows, usually 6 to 24 feet apart.

Drip torch: Portable equipment for applying flammable liquids giving a residual flame upon ignition; primarily used in prescribed burning

Drought (drouth): (1) A prolonged chronic shortage of water, as compared with the norm, often associated with high temperatures and winds during spring, summer and fall; (2) a period without precipitation during which the soil water content is reduced to such an extent that plants suffer from lack of water

Dugout: (1) An artificially constructed depression that collects and stores water and differs from a reservoir in that a dam is not relied upon to impound water (cf. stock pond); (2) a large hole dug in the ground, frequently on the side of a hill, and often covered with logs and sod, used as a dwelling or shelter

Ecological site: A kind of land with a specific potential natural community and specific physical site characteristics, differing from other kinds of land in its ability to produce vegetation and to respond to management (Syn. ecological type, ecological response unit. cf. range site)

Ecological status: The present state of vegetation and soil protection of an ecological site in relation to the potential natural community for the site. Vegetation status is the expression of the relative degree of which the kinds, proportions and amounts of plants in a community resemble that of the potential natural community. If classes or ratings are used, they should be described in ecological rather than utilization terms. For example, some agencies are utilizing four classes of ecological status ratings (early seral, midseral, late seral potential natural community) of vegetation corresponding to 0 to 25, 26 to 50, 51 to 75 and 76 to I00 percent of the potential natural community standard. Soil status is a measure of present vegetation and litter cover relative to the amount of cover needed on the site to prevent accelerated erosion. This term is not used by all agencies. (cf. range condition)

Ecological type: A land classification category that is more specific than a phase of a habitat type. Ecological types commonly are used to differentiate habitat phases into categories of land that differ in their ability to produce vegetation or their response to management. (Syn. ecological response unit, ecological site)

Ecology: The study of the interrelationships of organisms with their environment

Ecosystem: Organisms, together with their abiotic environment, forming an interacting system, inhabiting an identifiable space

Ecotone: A transition area of vegetation between two communities, having characteristics of both kinds of neighboring vegetation as well as characteristics of its own; varies in width depending on site and climatic factors

Ecotype: A locally adapted population within a species that has certain genetically determined characteristics; interbreeding between ecotypes is not restricted (cf. biotype)

Enclosure: An area fenced to confine animals

Endemic: Native to or restricted to a particular area, region or country

Environment: The sum of all external conditions that affect an organism or community to influence its development or existence

Eradication (plant): Complete kill or removal of a noxious plant from an area; includes all plant structures capable of sexual or vegetative reproduction

Erosion: (v.) Detachment and movement of soil or rock fragments by water, wind, ice or gravity; (n.) the land surface worn away by running water, wind, ice or other geological agents, including such processes as gravitational creep

Essential element: A chemical element necessary for the life of an organism

Evergreen (plant): A plant that has leaves all year round and generally sheds them in a single season after new leaves of the current growing season have matured (cf. deciduous)

Evapotranspiration: The actual total loss of water by evaporation from soil, water bodies and transpiration from vegetation in a given area with time

Exclosure: An area fenced to exclude animals

Exotic: An organism or species that is not native to the region in which it is found

Exposure: Direction of slope with respect to points of a compass

Fauna: The animal life of a region; a listing of animal species of a region

Feces: Waste material voided through the anus

Fibrous root system: A plant root system having a large number of small, finely divided, widely spreading roots, but no large taproots; typified by grass root system (cf. taproot system)

Flushing: Improving the nutrition of female breeding animals prior to and during the breeding season to stimulate ovulation

Flora: (1) The plant species of an area; (2) a simple list of plant species or a taxonomic manual

Foliage: The green or live leaves of plants; mass leaves, leafage

Forage: (n.) Browse and herbage that is available and may provide food for grazing animals or be harvested for feeding; (v.) to search for or consume forage (Syn. Graze)

Forage production: The weight of forage that is produced in a designated period of time on a given area. The weight may be expressed as green, air-dry or oven-dry. The term also may be modified as to time of production, such as annual, current year’s growth or seasonal forage production.

Forage reserve: Standing forage specifically maintained for future or emergency use

Forb: Any broad-leafed herbaceous plant other than those in the Gramineae (or Poaceae), Cyperaceae and Juncacea families

Free range: Range open to grazing regardless of ownership and without payment of fees; not to be confused with open range

Frequency: The ratio between the number of sample units that contain a species and the total number of sample units

Fresh weight: The weight of plant materials at the time of harvest (Syn. green weight)

Full use: The maximum use during a grazing season that can be made of range forage under a given grazing program without inducing a downward trend in range condition or ecological status

Geographic information system (GIS): A spatial type of information management system that provides for the entry, storage, manipulation, retrieval and display of spatially oriented data

Graminoid: Grass or grasslike plant, such as Poa, Carex and Juncus species

Grass: A member of the family Gramineae (Poaceae)

Grassland: Land on which the vegetation is dominated by grasses, grasslike plants and/ or forbs (cf. dominant). Non-forest land shall be classified as grassland if herbaceous vegetation provides at least 80 percent of the canopy cover excluding trees. Lands not presently grassland that originally were or could become grassland through natural succession may be classified as potential natural grassland. (cf. prairie, rangeland)

Grasslike plant: A plant of the Cypeaceae or Juncacea families that vegetatively resembles a true grass of the Gramineae family

Gravel, cobble, stones: As defined in “Soil Taxonomy” (Soil Conservation Service, 1975): gravel (2 millimeters to 3 inches), cobble (3 to 10 inches), stones (more than 10 inches). (Note: For standard range inventory procedures, gravel smaller than 5 millimeters in diameter should be classed as bare ground in cover determinations)

Graze: (1) (vi.) The consumption of standing forage by livestock or wildlife; (2) (vt.) to put livestock to feed on standing forage

Grazer: A grazing animal.

Grazier: A person who manages grazing animals.

Grazing: (vt.) To graze

Grazing behavior: The foraging response elicited from an herbivore by its interaction with its surrounding environment

Grazing capacity: The total number of animals that may be sustained on a given area based on total forage resources available, including harvested roughage and concentrates (cf. carrying capacity) Grazing distribution: Dispersion of livestock grazing within a management unit or area

Grazing land: A collective term that includes all lands having plants harvestable by grazing without reference to land tenant, other land uses, management or treatment practices

Grazing management: The manipulation of grazing and browsing animals to accomplish a desired result

Grazing management plan: A program of action designed to secure the best practicable use of the forage resources with grazing or browsing animals

Grazing period: The length of time that animals are allowed to graze on a specific area

Grazing preference: (1) Selection of certain plants or plant parts, rather than others, by grazing animals; (2) in the administration of public lands, a basis upon which permits and licenses are issued for grazing use (cf. palatability, grazing privilege and grazing right)

Grazing pressure: An animal-to-forage relationship measured in terms of animal units per unit weight of forage at any instant (AU/T)

Grazing pressure index: An animal-to-forage relationship measured in terms of animal units per unit weight of forage during a period of time (AUM/T)

Grazing season: (1) On public lands, an established period for which grazing permits are issued; may be established on private land in a grazing management plan; (2) the time interval when animals are allowed to utilize a certain area

Grazing system: A specialization of grazing management that defines the periods of grazing and non-grazing. Descriptive common names may be used; however, the first usage of a grazing system name in a publication should be followed by a description using a standard format. This format should consist of at least the following: the number of pastures (or units), number of herds, length of grazing periods, and length of non-grazing periods for any given unit in the system, followed by an abbreviation of the unit time used. (cf. deferred grazing, deferred-rotation, rotation, rest-rotation, and short duration grazing)

Grazing unit: An area of rangeland, public or private, that is grazed as an entity

Ground cover: The percentage of material, other than bare ground, covering the land surface. It may include live and standing dead vegetation, litter, cobble, gravel, stones and bedrock. Ground cover plus bare ground would total 100 percent. (cf. foliar cover)

Growing season: In temperate climates, that portion of the year when temperature and moisture permit plant growth. In tropical climates, it is determined by availability of moisture.

Growth form: The characteristic shape or appearance of an organism

Gully: A furrow, channel or miniature valley, usually with steep sides through which water commonly flows during and immediately after rains or snowmelt

Habitat: The natural abode of a plant or animal, including all biotic, climatic and edaphic factors affecting life

Habitat type: The collective area that one plant association occupies or will come to occupy as succession advances. The habitat type is defined and described on the basis of the vegetation and its associated environment.

Half-shrub: A woody based perennial plant with annually produced stems which die each year

Hardiness: The ability to survive exposure to adverse conditions

Hardpan: A hardened soil layer in the lower A or in the B horizon caused by cementation of soil particles with organic matter or with materials such as silica, sesquioxides or calcium carbonate. The hardness does not change appreciably with changes in moisture content, and pieces of the hard layer do not crumble in water.

Harvest: Removal of animal or vegetation products from an area of land

Heavy grazing: A comparative term indicating that the stocking rate of a pasture is relatively greater than that of other pastures; often erroneously used to mean overuse (cf. light and moderate grazing)

Herb: Any flowering plant except those developing persistent woody stems above ground

Herbaceous: Vegetative growth with little or no woody component; non-woody vegetation, such as graminoids and forbs

Herbage: (1) Herbs taken collectively; (2) total aboveground biomass of herbaceous plants regardless of grazing preference or availability

Herbage disappearance rate: The rate per unit area at which herbage leaves the standing crop due to grazing, senescence or other causes; Unit: kg/ha/d, or lbs/ac/d

Herbicide: A phytotoxic chemical used for killing or inhibiting the growth of plants

Herbivore: An animal that subsists principally or entirely on plants or plant materials

Herd: An assemblage of animals usually of the same species

Holistic resource management: Holistic resource management (HRM) is a practical, goal-oriented approach to the management of the ecosystem, including the human, financial and biological resources on farms, ranches, public and tribal lands, as well as national parks, vital water catchments and other areas. HRM entails the use of a management model that incorporates a holistic view of land, people and dollars.

Hybrid: Offspring of a cross between genetically dissimilar individuals

Hybrid vigor: The increased performance (rate of gain) associated with F1 crossbreeding

Ice cream species: An exceptionally palatable species sought and grazed frequently by livestock or game animals. Such species often are over-utilized under proper grazing

Increaser: Plant species of the original vegetation that increase in relative amount, at least for a time, under continued disturbance to the norm; for example, heavy defoliation, fire, drought

Indicator species: (1) Species that indicate the presence of certain environmental conditions, seral stages or previous treatment; (2) one or more plant species selected to indicate a certain level of grazing use (cf. key species)

Infestation: Invasion by large numbers of parasites or pests

Infiltration: The flow of a fluid into a substance through pores or small openings. It denotes flow into a substance in contradistinction to the word percolation.

Infiltration rate: Maximum rate at which soil under specified conditions can absorb rain or shallow impounded water, expressed in quantity of water absorbed by the soil per unit of time; for example, inches/ hour

Interseeding: Seeding into an established vegetation cover; often is planting seeds into the center of narrow seedbed strips of variable spacing and prepared by mechanical or chemical methods

Introduced species: A species not a part of the original fauna or flora of the area in question (cf. native and resident species)

Invader: Plant species that were absent in undisturbed portions of the original vegetation of a specific range site and will invade or increase following disturbance or continued heavy grazing

Invasion: The migration of organisms from one area to another area and their establishment in the latter (cf. ecesis)

Key management species: Plant species on which management of a specific unit is based

Key species: (1) Forage species of sufficient abundance and palatability to justify its use as an indicator to the degree of use of associated species; (2) those species that must, because of their importance, be considered in the management program

Kind of animal: An animal species or species group such as sheep, cattle, goats, deer, horses, elk, and antelope (cf. class of animal)

Land: The total natural and cultural environment within which production takes place; a broader term than soil. In addition to soil, its attributes include other physical conditions, such as mineral deposits, climate and water supply; location in relation to centers of commerce, populations and other land; the size of the individual tracts or holdings; and existing plant cover, works of improvement and the like. Some use the term loosely in other senses: as defined above but without the economic or cultural criteria; especially in the expression “natural land;” as a synonym for “soil;” for the solid surface of the Earth; and also for earthly surface formations, especially in geomorphologic expression “land form.”

Land use planning: The process by which decisions are made on future land uses for extended time periods that are deemed to best serve the general welfare. Decision-making authorities on land uses usually are vested in state and local governmental units, but citizen participation in the planning process is essential for proper understanding and implementation, usually through zoning ordinances.

Light grazing: A comparative term indicating that the stocking rate of one pasture is relatively less than that of other pastures; often erroneously used to mean underuse (cf. heavy and moderate grazing)

Lime: (1) Calcium oxide; (2) all limestone derived materials applied to neutralize acid soils

Limiting factor: Any environmental factor that exists at suboptimal level and thereby prevents an organism from reaching its full biotic potential

Livestock: Domestic animals

Management area: An area for which a single management plan is developed and applied

Management objective: The objectives for which rangeland and rangeland resources are managed, which include specified uses, accompanied by a description of the desired vegetation and the expected products and/or values

Management plan: A program of action designed to reach a given set of objectives

Marginal land: Land of questionable physical or economic capabilities for sustaining a specific use

Marsh: Flat, wet, treeless areas usually covered by standing water and supporting a native growth of grasses and grasslike plants

Mast: Nuts, acorns and similar products consumed by animals

Meadow: (1) An area of perennial herbaceous vegetation, usually grass or grasslike, used primarily for hay production; (2) openings in forests and grasslands of exceptional productivity in arid regions, usually resulting from high water content of the soil, as in stream-side situations and areas having a perched water table (cf. dry and wet meadow)

Moderate grazing: A comparative term indicating that the stocking rate of a pasture is between the rates of other pastures; often erroneously used to mean proper use (cf. heavy and light grazing)

Monitoring: The orderly collection, analysis and interpretation of resource data to evaluate progress toward meeting management objectives

Morphology: The form and structure of an organism with special emphasis on external features

Mulch: (n.) (1) A layer of dead plant material on the soil surface (cf. fresh and humic mulch); (2) an artificial layer of material such as paper or plastic on the soil surface; (v.) cultural practice of placing rock, straw, asphalt, plastic or other material on the soil’s surface as a surface cover

Multiple use: Use of range for more than one purpose; for example, grazing of livestock, wildlife production, recreation, watershed and timber production; not necessarily the combination of uses that will yield the highest economic return or greatest unit output

Native species: A species that is a part of the original fauna or flora of the area in question (Syn. indigenous. cf. introduced and resident species)

Naturalized species: A species not native to an area that adapted to the area and has established a stable or expanding population; does not require artificial inputs for survival and reproduction; for example, cheatgrass, Kentucky bluegrass, starling

Nonuse: (1) Absence of grazing use on current year’s forage production; (2) lack of exercise, of a grazing privilege on grazing lands; (3) an authorization to refrain, temporarily, from placing livestock on public ranges without loss of preference for future consideration

Noxious species: A plant species that is undesirable because it conflicts, restricts or otherwise causes problems under management objectives; not to be confused with species declared noxious by laws concerned with plants that are weedy in cultivated crops and on range

Nurse crop: A temporary crop seeded at or near the time primary plant species are seeded to provide protection and otherwise help ensure establishment of the latter (cf. companion crop, preparation crop)

Nutritive value: Relative capacity of given forage or other feedstuff to furnish nutrition for animals. In range management, the term usually is prefixed by high, low or moderate.

Open range: (1) Range that has not been fenced into management units; (2) all suitable rangeland of an area upon which grazing is permitted; (3) un-timbered rangeland; (4) range on which the livestock owner has unlimited access without benefit of land ownership or leasing

Organism: Any living entity; plant, animal, fungus, etc.

Outcrop: The exposure of bedrock or strata projecting through the overlying cover of detritus and soil

Oven dry weight: The weight of a substance after it has been dried in an oven at a specific temperature to equilibrium

Overgrazing: Continued heavy grazing that exceeds the recovery capacity of the community and creates a deteriorated range (cf. overuse)

Overland flow: Surface runoff of water following a precipitation event (cf. runoff)

Overstocking: Placing a number of animals on a given area that will result in overuse if continued to the end of the planned grazing period

Overstory: The upper canopy or canopies of plants; usually refers to trees, tall shrubs and vines

Overuse: Utilizing an excessive amount of the current year’s growth which, if continued, will result in range deterioration (cf. overgrazing)

Paddock: (1) One of the subdivisions or subunits of the entire pasture unit, or grazing area enclosed and separated from other areas by fencing or other barriers; (2) a subdivision or subunit of an entire grazing unit (cell) often involved in controlled grazing of some manner; (3) a relatively small enclosure used as an exercise and saddling area for horses, generally adjacent to stalls or stable (Syn. Pasture; cf. cell)

Palatability: The relish with which a particular species or plant part is consumed by an animal

Pan (soils): Horizon or layer in soils that is strongly compacted, indurated or very high in clay content (cf. caliche, claypan, hardpan)

Pasture: (1) A grazing area enclosed and separated from other areas by fencing or other barriers; the management unit for grazing land; (2) forage plants used as food for grazing animals; (3) any area devoted to the production of forage, native or introduced, and harvested by grazing; (4) a group of subunits grazed within a rotational grazing system

Pastureland: Grazing lands, planted primarily to introduced or domesticated native forage species, that receive periodic renovation and/or cultural treatments, such as tillage, fertilization, mowing, weed control and irrigation; not in rotation with crops

Percent use: Grazing use of current growth, usually expressed as a percent of the current growth (by weight), that has been removed (cf. degree of use)

Perennial plant: A plant that has a life span of three or more years

Pesticide: Any chemical agent such as herbicide, fungicide or insecticide used for control of specific organisms

Phenotype: The physical appearance of an individual as contrasted with genetic makeup or genotype

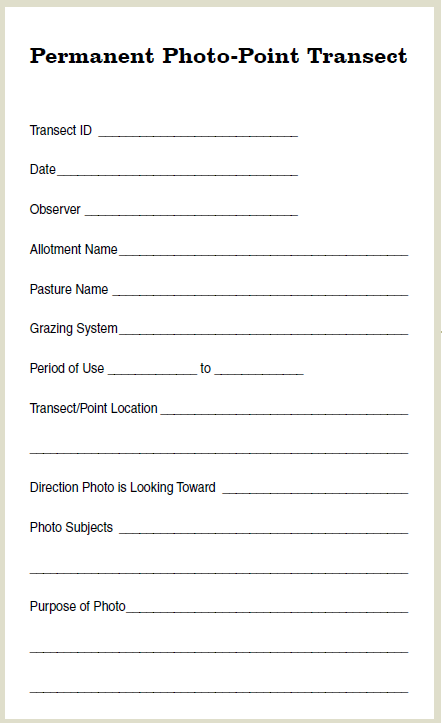

Photopoint: An identified point from which photographs are taken at periodic intervals

Photosensitization: A noncontagious disease resulting from the abnormal reaction of light-colored skin to sunlight after a photodynamic agent has been absorbed through the animal’s system. Grazing certain kinds of vegetation or ingesting certain molds under specific conditions causes photosensitization.

Pioneer species: The first species or community to colonize or recolonize a barren or disturbed area in primary or secondary succession

Pitting: Making shallow pits or basins of suitable capacity and distribution on range to reduce overland flow from rainfall or snowmelt

Plain: A broad stretch of relatively level treeless land

Plant vigor: Plant health

Poisonous plant: A plant containing or producing substances that causes sickness, death or a deviation from the normal state of health of animals

Prairie: An extensive tract of level or rolling land that originally was treeless and grass-covered (cf. grassIand, rangeland)

Precipitation: Condensation from the atmosphere, falling as rainfall, snow, hail or sleet

Preferred species: Species that are preferred by animals and are grazed by first choice

Prescribed burning: The use of fire as a management tool under specified conditions for burning a predetermined area (cf. maintenance burning)

Primary production: The conversion of solar energy to chemical energy through the process of photosynthesis. It is represented by the total quantity of organic material produced within a given period by vegetation.

Primary productivity: The rate of conversion of solar to chemical energy through the process of photosynthesis

Primary range: Areas that animal prefer to use when management is limited. Primary range will be overused before secondary range is fully used.

Pristine: A state of ecological stability or condition existing in the absence of direct disturbance by modern man

Productivity: The rate of production per unit area, usually expressed in terms of weight or energy

Proper grazing: The act of continuously obtaining proper use

Proper stocking: Placing a number of animals on a given area that will result in proper use at the end of the planned grazing period. Continued proper stocking will lead to proper grazing.

Proper use: A degree of utilization of current year’s growth which, if continued, will achieve management objectives and maintain or improve the long-term productivity of the site. Proper use varies with time and systems of grazing. (Syn. proper utilization, proper grazing use; cf. allowable use)

PLS: Abbreviation for pure live seed

Pure live seed: Purity and germination of seed expressed in percent; may be calculated by formula: PLS = % germination X % purity / 100; for example, 91 X 96/100 = 87.36 percent (Abbr., PLS; cf. seed purity)

Range: (n.) Any land supporting vegetation suitable for grazing, including rangeland, grazable woodland and shrubland; range is not a use; (adj.) modifies resources, products, activities, practices and phenomena pertaining to rangeland (cf. rangeIand, forested range, grazable woodland, shrubland)

Range appraisal: The classification and valuation of rangeland from an economic or production standpoint

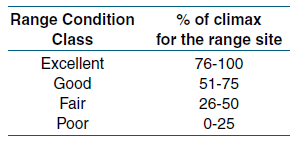

Range condition: (a) A generic term relating to present status of a unit of range in terms of specific values or potentials. Specific values or potentials must be stated; (b) some agencies define range condition as follows: the present state of vegetation of a range site in relation to the climax (natural potential) plant community for that site. It is an expression of the relative degree to which the kinds, proportions and amounts of plants in a plant community resemble that of the climax plant community for the site. (cf. ecological status and resource value rating)

Range condition class: Confusion has existed regarding the definition and use of this term. (1) The following definition fits the thinking expressed in the definition Range Condition (a) above: One of a series of arbitrary categories used to classify ecological status of a specific range site in relation to its potential (early, mid, late seral or PNC) or classify management-oriented value categories for specific potentials; for example, good condition spring cattle range. (2) Some agencies consider range condition class in the context of Range Condition (b) above as follows:

Range management: A distinct discipline founded on ecological principles and dealing with the use of rangelands and range resources for a variety of purposes. These purposes include use as watersheds, wildlife habitat, grazing by livestock, recreation and aesthetics, as well as other associated uses.

Range readiness: The defined stage of plant growth at which grazing may begin under a specific management plan without permanent damage to vegetation or soil; usually applied to seasonal range

Range seeding: The process of establishing vegetation by the artificial dissemination of seed

Range site: Synonymous with ecological site when referring to rangeland; an area of rangeland that has the potential to produce and sustain distinctive kinds and amounts of vegetation to result in a characteristic plant community under its particular combination of environmental factors, particularly climate, soils and associated native biota. Some agencies use range site based on the climax concept, not potential natural community. (cf. vegetative type)

Rangeland: Land on which the native vegetation (climax or natural potential) is predominantly grasses, grasslike plants, forbs or shrubs; includes lands revegetated naturally or artificially when routine management of that vegetation is accomplished mainly through manipulation of grazing. Rangelands include natural grasslands, savannas, shrublands, most deserts, tundra, alpine communities, coastal marshes and wet meadows. (cf. forestland, range)

Rangeland inventory: (1) The systematic acquisition and analysis of resource information needed for planning and for management of rangeland; (2) the information acquired through rangeland inventory

Rangeland renovation: Improving rangeland by mechanical, chemical or other means

RecIamation: Restoration of a site or resource to a desired condition to achieve management objectives or stated goals (cf. revegetation)

Remote sensing: The measurement or acquisition of information of some property, object or phenomenon by a recording device that is not in physical or intimate contact with the object or phenomenon under study; often involves aerial photography or satellite imagery

Reseeding: Syn. range seeding

Rest: Leaving an area ungrazed, thereby foregoing grazing of one forage crop. Normally, rest implies absence of grazing for a full growing season or during a critical portion of plant development, or seed production (cf. deferment)

Rest period: A time period of no grazing included as part of a grazing system

Rest-rotation: A grazing management scheme in which rest periods for individual pastures, paddocks or grazing units, generally for the full growing season, are incorporated into a grazing rotation (cf. grazing system)

Rhizome: A horizontal underground stem usually sending out roots and above-ground shoots from the nodes

Riparian: Referring to or relating to areas adjacent to water or influenced by free water associated with streams or rivers on geologic surfaces occupying the lowest position on a watershed

Riparian species: Plant species occurring in the riparian zone. Obligate species require the environmental conditions in the riparian zone; facultative species tolerate the environmental conditions and may occur away from the riparian zone.

Riparian zone: The banks and adjacent areas of water bodies, water courses, seeps and springs whose waters provide soil moisture sufficiently in excess of that otherwise available locally so as to provide a moister habitat than that of contiguous flood plains and uplands

Ripping: The mechanical penetration and sheering of range soils to depths of 8 to 18 inches for the purpose of breaking hardpan layers to facilitate penetration of plant roots, water, organic matter and nutrients; a range improvement practice used where native grasses of a rhizomatous nature can spread into the ripped soil (cf. chiseling)

Rotation grazing: A grazing scheme in which animals are moved from one grazing unit (paddock) in the same group of grazing units to another without regard to specific graze:rest periods or levels of plant defoliation (cf. grazing system)

Roughage: Plant materials containing a low proportion of nutrients per unit of weight and usually bulky and coarse, high in fiber and low in total digestible nutrients. Roughage may be classed as dry or green.

Rumen: The large first compartment of the stomach of a ruminant from which ingested food is regurgitated for rechewing and in which digestion is aided by symbiotic action of microbes

Ruminant: Even-toed, hoofed mammals that chew the cud and have a four-chamber stomach, or Ruminantia

Runoff: The total stream discharge of water, including surface and subsurface flow, usually expressed in acre-feet of water yield

Sacrifice area: A portion of the range; respective of site, that is unavoidably overgrazed to obtain efficient overall use of the management area

Seasonlong grazing: See Continuous Grazing

Seasonal grazing: Grazing restricted to a specific season. Synonymous with season of use; i.e. spring, summer, fall, winter.

Seasonal use: (1) Synonymous with seasonal grazing; (2) seasonal preference of certain plant species by animals

Secondary range: Range that is used lightly or unused by livestock under minimal management and ordinarily will not be fully used until the primary range has been overused

Seed: A fertilized, ripened ovule of a flowering plant

Seed certification: A system whereby seed of plant cultivars is produced, harvested and marketed under authorized regulation toe seed of high quality and genetic purity

Seed, dormant: Live seed in a non-germinated condition because of (1) internal inhibitions in the seed, or hard seed, or (2) unfavorable environmental conditions

Seed inoculation: Treatment of legume seed with rhizobium bacteria before planting to enhance subsequent nitrogen fixation

Seedbed preparation: Soil treatment prior to seeding to: (1) reduce or eliminate existing vegetation, (2) reduce the effective supply of weed seed, (3) modify physical soil characteristics and (4) enhance temperature and water characteristics of the microenvironment

Seed purity: The percentage of the desired species in relation to the total quantity, including other species, weed seed and foreign matter (cf. pure live seed)

Seep: Wet areas, normally not flowing, arising from an underground water source

Selective grazing: The grazing of certain plant species, individual plants or plant parts on the range to the exclusion of others

Short-duration grazing: Grazing management whereby relatively short periods (days) of grazing and associated nongrazing are applied to range or pasture units. Periods of grazing and nongrazing are based upon plant growth characteristics. Short-duration grazing has nothing to do with intensity of grazing use. (cf. grazing system)

Shrub: A plant that has persistent, woody stems and a relatively low growth habit, and that generally produces several basal shoots instead of a single bole. It differs from a tree by its low stature (generally less than 5 meters, or 16 feet) and non-arborescent form.

Shrubland: Any land on which shrubs dominate the vegetation

Similarity index: The percentage of a specific vegetation state plant community that is presently on the site

Slope: A slant or incline of the land surface measured in degrees from the horizontal, or in the percent (defined as the number of feet or meters change in elevation per 100 of the same units of horizontal distance); may be further characterized by direction (exposure)

Sod: Vegetation that grows so as to form a mat of soil and vegetation (Syn. Turf)

Sod grasses: Stoloniferous or rhizomatous grasses that form a sod or turf (cf. bunchgrass)

Soil: (1) The unconsolidated mineral and organic material on the immediate surface of the Earth that serves as a natural medium for the growth of land plants; (2) the unconsolidated mineral matter on the surface of the Earth that has been subjected to and influenced by genetic and environmental factors of parent material, climate (including moisture and temperature effects), macro- and micro-organisms, and topography, all acting during a period of time and producing a product-soil-that differs from the material from which it was derived in many physical, chemical, biological, and morphological properties and characteristics

Soil condition class: One of a series of arbitrary categories based principally on the amount of ground cover weighted by the degree of accelerated erosion used to identify soil stability

Species: A taxon or rank species; in the hierarchy or biological classification, the category below genus

Species composition: The proportions of various plant species in relation to the total on a given area. It may be expressed in terms of cover, density, weight, etc.

Spot grazing: Repeated grazing of small areas while adjacent areas are lightly grazed or unused

Spring: Flowing water originating from an underground source

Stand: An existing plant community with definitive bounds that is relatively uniform in composition, structural and site conditions; thus, it may serve as a local example of a community type

Standing crop: The total amount of plant material per unit of space at a given time; often is divided into above-ground and below-ground portions and further may be modified by the descriptors “dead,” or :live” to more accurately define the specific type of biomass

Stem: The culm or branch of a plant

Stock: Livestock

Stocking density: The relationship between number of animals and area of land at any instant of time. It may be expressed as animal-units per acre, animal-units per section or AU/ ha. (cf. stocking rate)

Stocking rate: The number of specific kinds and classes of animals grazing or utilizing a unit of land for a specified time period; may be expressed as animal unit months or animal unit days per acre, hectare or section, or the reciprocal (area of land/animal unit month or day). When dual use is practiced (for example, cattle and sheep), stocking rate often is expressed as animal unit months/unit of land or the reciprocal. (Syn. stocking Ievel; cf. stocking density)

Stockpiling: Allowing standing forage to accumulate for grazing at a later period, often for fall and winter grazing after dormancy (cf. cured forage)

Stock pond: A water impoundment made by constructing a dam or by excavating a dugout, or both, to provide water for livestock and wildlife (cf. catchment, guzzler, drink tank)

Stock water development: Development of a new or improved source of stock water supply, such as well, spring or pond, together with storage and delivery system

Stolon: A horizontal stem that grows along the surface of the soil and roots at the nodes

Stubble: The basal portion of herbaceous plants remaining after the top portion has been harvested artificially or by gazing animals

Submarginal land: Land that is physically or economically incapable of indefinitely sustaining a certain use

Succession: The progressive replacement of plant communities on a site that leads to the potential natural plant community; for example, attaining stability. Primary succession entails simultaneous successions of soil from parent material and vegetation. Secondary succession occurs following disturbances on sites that previously supported vegetation and entails plant succession on a more mature soil.

Suitable range: (1) Range accessible to a specific kind of animal and that can be grazed on a sustained yield basis without damage to the resource; (2) the limits of adaptability of plant or animal species. One U.S. agency utilizes the term as follows: Land that is accessible or that can become accessible to livestock, that produces forage or has inherent forage producing capabilities and that can be grazed on a sustained yield basis under reasonable management goals. Suitable range includes rangeland and forest land with a grazeable understory that is contained in grazing allotments.

Supplement: Nutritional additive (salt, protein, phosphorus, etc.) intended to remedy deficiencies of the range diet

Supplemental feeding: Supplying concentrates or harvested feed to correct deficiencies of the range diet; often erroneously used to mean emergency feeding (cf. maintenance feeding)

Surfactant: A surface active agent, or materials used in herbicide formulations to bring about emulsifiability, spreading, wetting, sticking, dispersibility, solubilization or other surface modifying properties

Swale: An area of low and sometimes wet land

Taproot system: A plant root system dominated by a single large root, normally growing straight downward, from which most of the smaller roots spread out laterally (cf. fibrous root system)

Terracing: Mechanical movement of soil along the horizontal contour of a slope to produce an earthen dike to retain water and diminish the potential of soil erosion

Tiller: The asexual development of a new plant from a meristematic region of the parent plant

Total annual yield: The total annual production of all plant species of a plant community

Trace element: An element essential for normal growth and development of an organism but required only in minute quantities

Trampling: Treading underfoot; the damage to plants or soil brought about by movements or congestion of animals

Tree: A woody perennial; usually single-stemmed plant, that has a definite crown shape and reaches a mature height of at least 16 feet (5 meters). There is no clear-cut distinction between trees and shrubs. Some plants, such as oaks (Quecus spp.), may grow as trees or shrubs

Trend (range trend): Classes and Ecological Status Ratings: Trend in range condition or ecological status should be described as up, down or not apparent. “Up” represents a change toward climax or potential natural community, “down” represents a change away from climax or potential natural community and “not apparent” indicates no recognizable change. This category often is recorded as static or stable. No necessary correlation has been found among trends in resource value ratings, vegetation management status, range condition or ecological status

Trophic levels: The sequence of steps in a food chain or food pyramid from producer to primary, secondary or tertiary consumer

Turf: Syn. sod

Twice-over rotational grazing: A variation of the deferred-rotation grazing system that involves grazing three or more native pastures in rotation based on the growth stages of key species. Livestock are rotated through the grazing system faster than a deferred-rotation (once-over), allowing for periods of regrowth and recovery of vegetation, resulting in a second grazing period; thus, twice-over.

Undergrazing: The act of continued underuse

Understocking: Placing a number of animals on a given area that will result in underuse at the end of the planned grazing period

Understory: Plants growing beneath the canopy of other plants; usually refers to grasses, forbs and low shrubs under a tree or shrub canopy (cf. overstory)

Underuse: A degree of use less than proper use

Undesirable species: (1) Species that conflict with or do not contribute to the management objectives; (2) species that are not readily eaten by animals

Ungulate: A hoofed animal, including ruminants but also horses, tapirs, elephants, rhinoceroses and swine

Unsuitable range: Range that has no potential value for, or which should not be used for, a specific use because of permanent physical or biological restrictions. When unsuitable range is identified, the identification must specify what use or uses are unsuitable (for example, “unsuitable cattle range”).

Use: (1) The proportion of current years forage production that is consumed or destroyed by grazing animals; may refer to a single species or to the vegetation as a whole (Syn. degree of use); (2) utilization of range for a purpose such as grazing, bedding, shelter, trailing, watering, watershed, recreation, forestry, etc.

Utilization: Syn. use

Vegetation: Plants in general, or the sum total of the plant life above and below ground in an area (cf. vegetative)

Vegetation type: A kind of existing plant community with distinguishable characteristics described in terms of the present vegetation that dominates the aspect or physiognomy of the area

Vegetative: Relating to nutritive and growth function of plant life in contrast to sexual reproductive functions; of or relating to vegetation

Vegetative reproduction: Production of new plants by any asexual method

Vigor: Relates to the relative robustness of a plant in comparison to other individuals of the same species. It is reflected primarily by the size of a plant and its parts in relation to its age and the environment in which it is growing. (Syn. plant vigor; cf. hybrid vigor)

Virgin: Syn. pristine

Warm-season plant: (1) A plant that makes most or all its growth during the spring, summer or fall and is usually dormant in winter; (2) a plant that usually exhibits the C-4 photosynthetic pathway

Watershed: (1) A total area of land above a given point on a waterway that contributes runoff water to the flow at that point; (2) a major subdivision of a drainage basin

Weed: (1) Any plant growing where unwanted; (2) a plant having a negative value within a given management system

Wetlands: Areas characterized by soils that usually are saturated or ponded; hydric soils that support mostly water-loving plants (hydrophytic plants)

Wetland communities: Plant communities that occur on sites with soils typically saturated with or covered with water most of the growing season

Wet meadow: A meadow where the surface remains wet or moist throughout the growing season, usually characterized by sedges and rushes

Wildlife: Undomesticated vertebrate animals considered collectively, with the exception of fish (cf. game)

Winter range: Range that is grazed during the winter months

Wolf plant: (1) An individual plant that generally is considered palatable but is not grazed by livestock; (2) an isolated plant growing to extraordinary size, usually from lack of competition or utilization

Woodland: A land area occupied by trees; a forest, woods

Woody: A term used in reference to trees, shrubs or browse that characteristically contains persistent ligneous material

Xeric: Having very little moisture; tolerating or adapted to dry conditions

Yearling: An animal approximately one year of age. A short yearling is from 9 to 12 months of age and a long yearling is from 12 to 18 months.

Yield: (1) The quantity of a product in a given space and/or time; (2) the harvested portion of a product (Syn. production, total annuaI yieId or runoff)

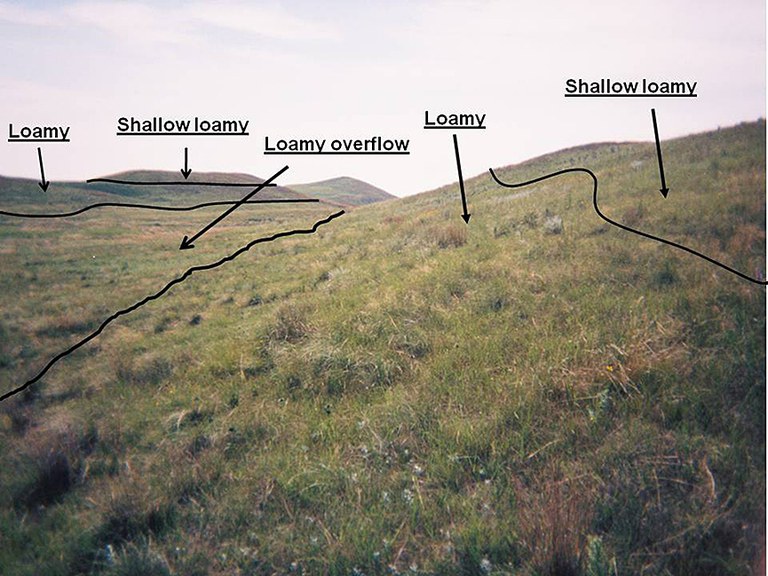

Ecological Sites

An ecological site is a distinctive kind of rangeland based on present or potential natural vegetation, potential productivity and/or soils, and other environmental factors. The kind and amount of vegetation produced on an ecological site will vary in an area due to soil type differences and landscape position (Figure 1).

To help identify ecological sites, the most common sites are illustrated below with location found in the landscape, major vegetation species associated with the site and recommended stocking rate for sites in high good to excellent condition. Lowest levels are for western North Dakota and highest levels for eastern North Dakota and western Minnesota.

Tip: See publication “Ecological Sites of North Dakota” (R1556) for detailed plant community and soil description, and photos of selected sites.

Tip: Complete versions of ecological site descriptions are available on the Web and ecological site maps for your area of interest are available via Web Soil Survey.

Clayey

Location: On very fine-textured soils occurring on flat to gentle undulating uplands with slopes of 0 to 25 percent.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: green needlegrass, porcupine grass, western wheatgrass, prairie Junegrass, blue grama, buffalo grass, western ragweed, silverleaf scurfpea, cudweed sagewort, prairie coneflower, goldenrod species, fringed sagewort, western snowberry, lead plant, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.6 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.8 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Claypan

Location: On very fine to fine-textured soils occurring on flat to undulating uplands, with upland sites containing “benches” and slopes 0 to 25 percent. Subsurface soil layers are restrictive to water movement and root penetration at 6 to 18 inches below soil surface.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: western wheatgrass, green needlegrass, blue grama, sandberg bluegrass, prairie Junegrass, heath aster, western yarrow, silverleaf scurfpea, wild onion, cudweed sagewort, scarlet globemallow, Missouri goldenrod, fringed sagewort, broom snakeweed, cactus.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.4 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.6 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Loamy

Location: On fine-textured soils occurring on gentle undulating to strongly rolling uplands and high stream terraces.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: green needlegrass, western wheatgrass, needle-and-thread, blue grama, upland sedges, western ragweed, silverleaf scurfpea, prairie coneflower, fringed sagewort, western snowberry, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.7 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.9 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Loamy Overflow

Location: On nearly level swales and depressions receiving additional moisture from adjacent slopes.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: big bluestem, switchgrass, green needlegrass, western wheatgrass, porcupine grass, Indiangrass, goldenrod species, cudweed sagewort, American licorice, western snowberry.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.9 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 1.2 AUMs/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Saline Lowland

Location: On saline soils occurring in depressions and along stream channels that receive additional moisture.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: western wheatgrass, nuttall alkaligrass, slender wheatgrass, inland saltgrass, foxtail barley, silverweed cinquefoil, pursh seepweed, curly dock.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.7 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 1.1 AUMs/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Sands

Location: On loamy, fine-sand-textured soils occurring on nearly level to rolling landscapes.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: needle-and-thread, prairie sandreed, sand dropseed, blue grama, upland sedges, western wheatgrass, purple prairie clover, green sagewort, Missouri goldenrod, fringed sagewort, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.7 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.8 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Sandy

Location: On fine sandy loam-textured soils occurring on nearly level to strongly rolling uplands and river terraces.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: needle-and-thread, prairie sandreed, green needlegrass, western wheatgrass, blue grama, upland sedges, western ragweed, green sagewort, Missouri goldenrod, fringed sagewort, prairie coneflower, heath aster, lead plant, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.7 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.9 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Shallow Gravel

Location: On medium to moderately coarse-textured soils overlying sand and gravel on nearly level to gently sloping uplands and stream terraces. Subsurface soil layers are restrictive to root penetration at 14 to 20 inches below soil surface.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: needle-and-thread, western wheatgrass, blue grama, prairie Junegrass, upland sedges, rush skeletonweed, dotted gayfeather, black samson, fringed sagewort, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.4 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.6 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Thin Claypan

Location: On very fine to fine-textured soils occurring on flat to undulating uplands, with upland sites containing “benches” and slopes 0 to 25 percent. Subsurface soil layers are restrictive to water movement and root penetration at surface to 6 inches below soil surface.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: western wheatgrass, blue grama, sandberg bluegrass, inland saltgrass, buffalo grass, sedges, health aster, western yarrow, wild onion, cudweed sagewort, scarlet globemallow, fringed sagewort, broom snakeweed, cactus.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.2 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.4 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Thin Loamy

Location: On medium-textured soils occurring on hill tops and steep uplands.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: little bluestem, sideoats grama, needle-and-thread, prairie sandreed, western wheatgrass, porcupine grass, plains muhly, blue grama, upland sedges, black samson, dotted gayfeather, Missouri goldenrod, purple prairieclover, prairie rose, broom snakeweed.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.5 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.7 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Very Shallow

Location: On medium to moderately coarse-textured soils overlying sand and gravel on nearly level to gently sloping uplands and stream terraces. Subsurface soil layers are restrictive to root penetration at surface to 14 inches below soil surface.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: little bluestem, needle-and-thread, plains muhly, blue grama, prairie Junegrass, upland sedges, dotted gayfeather, American pasqueflower, hairy goldaster, heath aster, black samson, fringed sagewort, prairie rose.

Estimated stocking rate: 0.2 AUM/acre (western North Dakota) to 0.4 AUM/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Wet Meadow

Location: On poorly drained medium- and fine-textured soils occurring in swales and depressions of rolling prairies.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: prairie cordgrass, northern reedgrass, switchgrass, fowl bluegrass, lowland sedges, baltic rush, common wild mint, tall white aster, curly dock.

Estimated stocking rate: 1.2 AUMs/acre (western North Dakota) to 1.4 AUMs/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Wet Land (Shallow Marsh)

Location: On poorly drained fine-textured soils occurring in shallow basins and depressions of upland prairies.

Major plant species in reference plant community phase: common reedgrass, prairie cordgrass, cattails, reed canarygrass, northern reedgrass, lowland sedges, baltic rush, smartweed species, curly dock, willow species.

Estimated stocking rate: 1.6 AUMs/acre (western North Dakota) to 1.8 AUMs/acre (eastern North Dakota, western Minnesota).

Native Range Plants

Native range plants include species that are a part of the original flora of the area in question. Listed on the following pages are common native range plants found in North Dakota and eastern Minnesota with a short description, season of growth, site on which they are found, forage value and their response to grazing. Plant name, characteristics and a detailed description can be found on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s PLANTS Database.

Grasses

Bearded wheatgrass

This cool-season, midstatured, short-lived perennial bunchgrass can be found growing on a variety of moist to dry sites, including loamy overflow, loamy, open woodlands and meadows. It usually is scattered throughout the plant community but can be abundant locally. The basal leaves of bearded wheatgrass are soft and palatable to all classes of livestock. It is considered a decreaser with heavy-grazing pressure. The leaves provide good forage for small mammals, rabbits, white-tailed deer and mule deer during most seasons. Many songbirds use the seeds to a lesser extent because of the presence of awns.

Big bluestem

This is a warm-season, perennial, tall-statured, sod-forming grass found on moist soils and ecological sites. It potentially is abundant on loamy overflow and subirrigated ecological sites. This grass decreases with overgrazing, frequently being replaced by less productive mid and short grass species. Big bluestem is very palatable and nutritious to all classes of livestock when actively growing but becomes coarse late in the season and quality declines.

Blue grama

This is a warm-season, perennial, short-statured bunchgrass found on drier upland sites, including sandy, gravelly, loamy, clayey and claypan soils. This grass increases with overgrazing, frequently replacing more productive mid and tall grass species, and often forming a dense sod intermixed with sedges. Blue grama is low-producing, very palatable and nutritious to all classes of livestock, even during the winter.

Buffalo grass

This warm-season, short-statured, stoloniferous perennial grass is one of the few grasses that reproduce by stolons (above-ground stems) in the northern Great Plains. It’s also unusual because those male and female flowers usually are produced on different plants. This species commonly is found on medium- to fine-textured soils associated with the clayey and claypan ecological sites. It is drought-tolerant and is considered an increaser with heavy grazing pressure, displacing higher-producing mid and tall grass species. Buffalo grass is very palatable and has good grazing value for all classes of livestock while providing fair to good grazing value for antelope and whitetail deer. The seeds have some feed value to bird species. Buffalo grass has received much attention as a low-growing grass for lawns, picnic areas, golf courses and airport runways due to its low maintenance requirements.

Canada wildrye

This cool-season, midstatured, short-lived perennial bunchgrass is adapted to a wide variety of soil textures and moistures but is best suited to dry or moist sandy, sand or gravelly sites. This species provides good forage for cattle and horses and fair forage for sheep during the spring. The plant’s feed value reduces dramatically as it matures and is used sparingly in the summer and fall. This species is considered a decreaser with grazing pressure.

Foxtail barley

This is a cool-season, perennial, mid-statured bunchgrass found on moist saline sites, often forming a distinctive ring around wetlands. This grass increases with overgrazing, frequently replacing productive mid and tall grasses, and wetland sedges. Due to increase levels of salts caused by a reduction of the more desirable plants species, foxtail barley will increase and dominate these sites. Once this occurs, returning these sites to their original status becomes difficult. Foxtail barley provides fair forage for cattle, horses and sheep when young but becomes unpalatable when mature.

Green needlegrass

A cool-season, perennial, this mid-stature bunchgrass is found on medium- and fine-textured soils. This species grows best on loamy soils but also is found on heavy clay soils. This grass decreases with overgrazing and early season grazing, frequently being replaced by less productive mid and short grass species. Green needlegrass is regarded as the most palatable of the needlegrasses and is nutritious to all classes of livestock.

Inland saltgrass

A warm-season, short-statured, perennial sod-former growing along roads and in low prairie sites, it is associated with moist alkaline or saline soils. Due to its poor palatability, inland saltgrass seldom is grazed and is considered an increaser under heavy grazing pressure. White-tailed deer use this plant’s foliage to a small extent, while some shorebirds and small rodents use the seeds.

Little bluestem

This is a warm-season, perennial, mid-statured bunchgrass found on dry ridges, hillsides and sand hill areas; it’s often associated with calcareous soils. The grass decreases with overgrazing, frequently being replaced by short grass, such as blue grama, sedges and broad-leaf species. The young shoots or new leaf tissue of little bluestem is regarded as palatable and often selected by grazing livestock. Older plant leaf tissue and seed stocks are avoided, giving the impression that the plant is not being grazed. Mature little bluestem has a classic red tinge in late summer and if ungrazed will become a wolf plant.

Lowland sedges (slough sedge and wooly sedge)

These are cool-season, mid- to tall-statured, perennial grasslike plants found in high-moisture sites such as wet meadow and wetland ecological sites. The number of different wetland sedge species is vast, all with varying degrees of palatability and response to grazing pressure. Slough sedge is considered very palatable to livestock and therefore considered a decreaser, while others are much less palatable and therefore tend to increase as grazing pressure reduces the more palatable species.

Needle-and-thread

This is a cool-season, perennial, mid-statured bunchgrass found on sandy and course-textured soils. This grass initially increases with grazing pressure, eventually decreasing with overgrazing, and is replaced by less productive mid and short grass species. Needle-and-thread is regarded as very palatable by all classes of livestock when grazed before plant maturity. If grazing occurs when seed or “needles” are present, they may be mechanically injurious, especially to sheep.

Plains muhly

It is a warm-season, short-statured, perennial bunchgrass that is found most commonly on stony or gravelly slopes of weakly developed soils along ridges and steep slopes. This species provides fair to good forage for all classes of livestock and is considered a decreaser under heavy grazing pressure. It provides good forage for white-tailed and mule deer, while wild turkeys and other birds use the seeds.

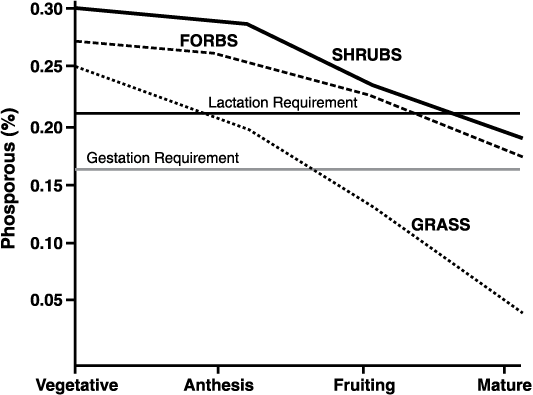

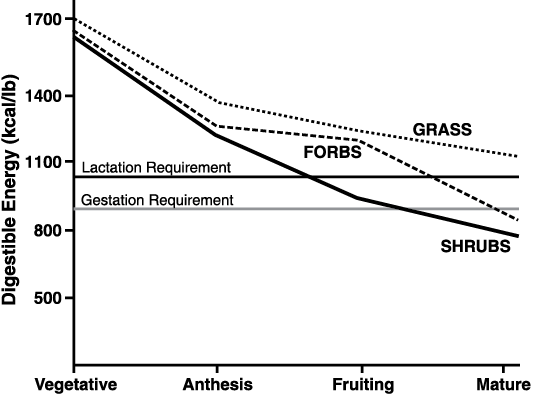

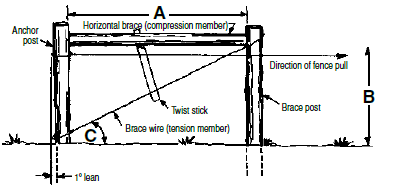

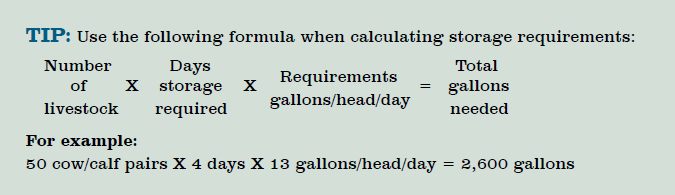

Porcupine grass