Preparing for a Successful Calving Season: Nutrition, Management and Health Programs (AS1207, Reviewed Sept. 2017)

Availability: Web only

Cow Nutrition Prior to Calving

During the last trimester of pregnancy, the fetus grows rapidly, placing increasing nutrient demands on the cow. In addition, cold weather increases the cow’s nutrient requirements. Body condition (fat cover) plays an important role in successfully wintering beef cows. Late weaning, overstocking, late supplementation, poor parasite control programs and inadequate winter rations all can lead to cows in poor body condition.

Why is Body Condition Important?

In spring-calving cow herds, body condition score (BCS) at calving is closely related to a number of production parameters in the cow and the newborn calf. Research clearly has demonstrated that spring-calving cows should be at BCS 5 or higher at calving time for optimal reproductive performance the following breeding season.

We also recommend that earlier-calving cows (January and February calving) and young cows (2- and 3-year-olds) calve in slightly higher BCS (5.5).

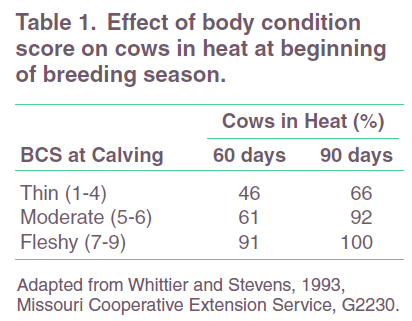

The time to improve BCS is during the fall, when weaning date and supplementation programs can impact body condition positively. Improving BCS following calving is very difficult and expensive because the nutrient demands in early lactation are very high. BCS at calving impacts the percentages of cows in heat 60 and 90 days following calving.

Table 1 shows that a greater percentage of cows with BCS 5 or greater at calving will be in heat at the start of the breeding season. If a cow is in heat at the beginning of the breeding season, the greater the chance that she will breed and calve early in the season, resulting in heavier weaning weights the subsequent fall.

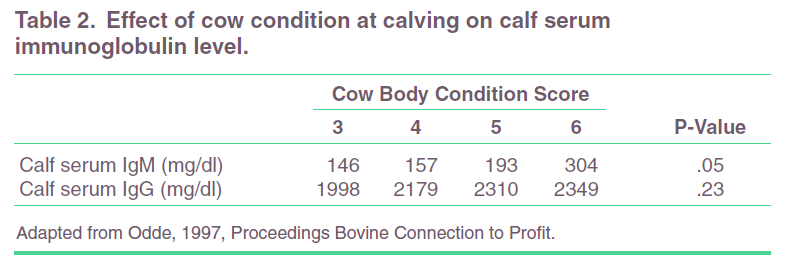

Table 2 shows the effect of cow body condition score at calving on colostral immunoglobulins.

Immunoglobulins are proteins that contain antibodies in the colostrum. These immunoglobulins help protect the calf from disease. Cows in higher body condition scores had more immunoglobulins in their colostrum than thinner cows. More immunoglobulin will result in a greater level of disease protection for the calf.

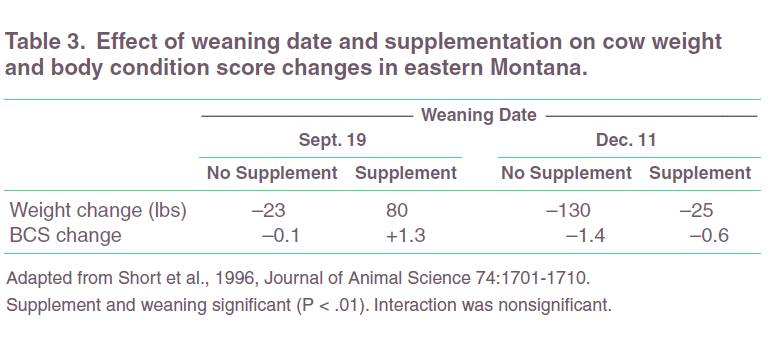

Table 3 shows data from research that investigated weaning dates and supplementation programs in eastern Montana. Calves were weaned and supplementation programs started in mid-September or mid-December. Cows that had calves weaned early and received supplements had improved body condition, compared with cows whose calves were weaned later and did not receive supplements. This research indicates weaning and supplementation can be used to improve BCS.

Early weaning or early supplementation allowed cows to maintain condition going into the winter. However, late weaning and lack of supplementation for cows nursing calves caused loss in weight and condition. Cows can gain body condition when calves are weaned and proper supplementation is provided.

Some research also indicates that supplementation with whole oilseeds (particularly safflower and soybean) in late gestation may have positive effects on calf survival and cow rebreeding performance. However, this response has not been seen with all research conducted with whole oilseed supplementation. Some variables that may impact this response include cow age (heifers vs. mature cows), nutrient requirements, weather conditions and forage quality.

Proper energy and protein nutrition is important for cows to maintain or increase body condition.

Adequate vitamin A also is necessary to ensure that calves are vigorous and healthy at birth. The precursor to vitamin A (carotene) is found in green, leafy forages and good-quality green hays.

Supplemental vitamin A can be given through fortified feeds, mineral mixes or injectable solutions containing the vitamin. Poor-quality forages, crop residues and weathered dormant grasses are deficient in vitamin A and require proper supplementation.

Deficiencies of vitamin A will result in weak, blind or stillborn calves, as well as respiratory problems, poor reproduction and poor gain.

Many other trace minerals and vitamins play a role in producing a healthy, vigorous calf. These include vitamin E, selenium, zinc and copper. Providing a good-quality trace mineral and vitamin supplementation program during late gestation is important to the cow and gestating calf.

Effect of Pre-calving Nutrition on Birth Weight and Calving Difficulty

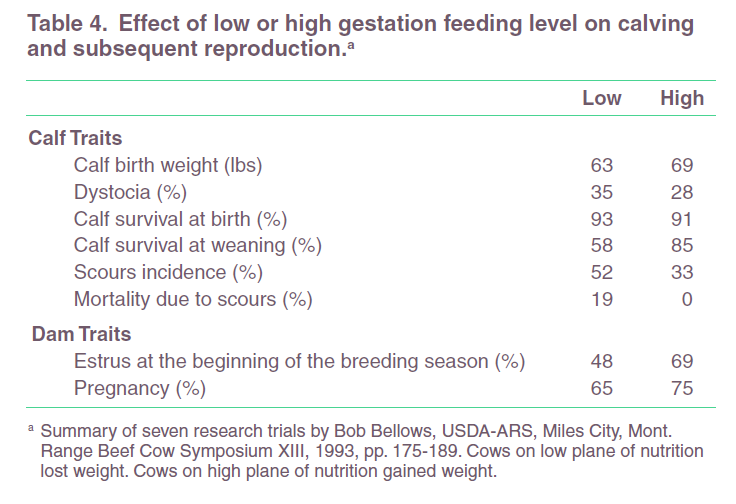

Reducing nutrient intake prior to calving will not reduce calf birth weight and subsequently reduce the incidence of dystocia or calving difficulty. Low planes of nutrition have been shown to have no effect or only slightly decrease birth weight.

Conversely, calving difficulty typically increases with reduced nutrient intake because the cow tends to be weaker. In addition, this practice results in weak calves that are less active immediately after birth.

Table 4 indicates that plane of nutrition during gestation plays a role in dystocia (calving difficulty) and calf survival. Even though cows fed on a high plane of nutrition during gestation had calves with higher birth weights, dystocia was lower, scours incidence and mortality were lower, calf survival at weaning was higher, and cows had higher pregnancy rates the following breeding season.

Overfeeding gestating beef cows can result in problems at calving time. Cows that are overconditioned deposit fat in the birth canal, resulting in calving difficulty. Extremely cold temperatures during late gestation also can

increase calf birth weight by increasing blood flow to the uterus, which results in increased nutrient supply to the fetus.

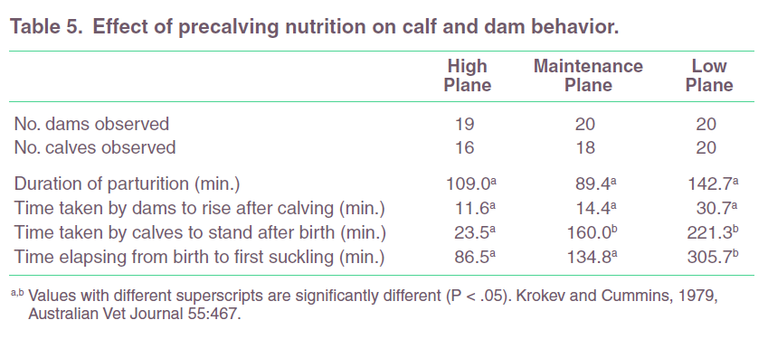

Effect of Pre-calving Nutrition on Calf and Dam Behavior

Research conducted in Australia investigated the effects of the pre-calving nutrition level on calf and dam behavior immediately following calving (Table 5). Calves born to dams on a low plane of nutrition took significantly longer to nurse than calves born to dams on a maintenance or high plane of nutrition.

The longer the calf takes to nurse, the higher the likelihood that colostrum absorption will not be adequate to protect the calf from disease.

Can Feeding Time Affect When Calves are Born?

(the Konefal Calving Method)

The time of day that cows are fed during the calving season can influence the time when calves are born. Cows fed at night tend to calve during the daylight hours (when you have an opportunity to watch them more closely).

This method of management was developed by Gus Konefal, a Manitoba Hereford breeder. The system involves feeding twice daily, once at 11 a.m. to noon, and again at 9:30 to 10 p.m. Based on his experience, the best results are obtained when the practice is started about one month before the first calf is born and continues for the duration of the calving season.

Konefal reported that when using this regime, 80 percent of his cows calved between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. Iowa State University research indicated similar results.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service, Miles City, Mont., also conducted a three-year study on feeding time. Their results were not as dramatic. However, the percentage of cows calving from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. was consistently 10 to 20 percent lower for the late-fed cows, compared with the early fed cows.

Similar research at the Brandon, Manitoba, research station indicated a 13.5 percent reduction in the number of cows calving between midnight and 7 a.m. However, research conducted in Indiana with dairy cows showed no particular benefit to night feeding.

Colostrum Management

Colostrum — a vital food for the newborn

Colostrum intake is critical for the newborn calf. At birth, a calf’s immune system is not fully developed. The calf must rely on colostrum from the cow until its own immune system is totally functional (about 1 to 2 months of age). Colostrum contains antibodies

or immunoglobulins necessary to provide the calf protection from disease.

For colostrum to be most effective, the calf should receive 1 quart within six hours after birth and a total of 2 to 3 quarts within 12 hours of birth. After this time, the gut begins to “close” and absorbing the antibodies found in the colostrum becomes more difficult for the calf.

At six hours after birth, calves absorbed 66 percent of the immunoglobulins in colostrum, but at 36 hours after birth, calves were able to absorb only 7 percent of the immunoglobulins.

Colostrum contains 22 percent solids, compared with 12 percent solids in normal whole cow’s milk. Much of the extra solid material in colostrum is immunoglobulin, but colostrum also is an important source of protein (casein), sugars in the form of lactose, fat, and vitamins A and E.

The volume of colostrum produced by a cow is affected by breed type (dairy breeds produce more than beef breeds) and cow age (mature cows produce more than heifers). However, higher colostral volumes in dairy breeds also are related to lower overall immunoglobulin concentrations in colostrum from these breeds.

Cows on higher planes of nutrition also produce more colostrum than cows on a low plane of nutrition.

Calves that have experienced a difficult or prolonged birth tend to take longer to stand and nurse, resulting in a weak calf that lacks the proper immunoglobulin protection necessary to fend off disease threats. These calves may need to be tube-fed to receive adequate amounts of colostrum.

Handling and Storing Colostrum

Some cows don’t produce an adequate amount of colostrum. The use of colostrum from other cows or stored colostrum sometimes is necessary to ensure that each calf receives adequate colostrum.

For optimum results, colostrum should be collected from cows within 24 hours of calving and fed fresh. Colostrum can be collected at calving, stored frozen and used at a later date as well.

To facilitate storage and thawing, you may want to consider storing colostrum in zipper-top freezer bags or freezer-safe containers. The bags or containers will store flat in the freezer, and you can use a size that makes thawing individual “servings” (1 or 2 quarts) of colostrum easier.

Colostrum should not be refrozen after being thawed.

Antibodies and immunoglobulins in colostrum are protein. Correct thawing is important to prevent colostrum from being damaged. Colostrum should be thawed slowly in a microwave or in warm water.

Here are two suggested methods:

1. Place frozen colostrum and its container in warm (110 F) water and stir every five minutes. The colostrum should be warmed to 104 to 110 F.

2. Thaw colostrum in a microwave oven. Set the oven at no more than 60 percent power for gentle thawing. Agitate or stir the colostrum frequently to assure even thawing and warming. This is important because many microwaves do not heat material evenly. Warm the colostrum to 104 F.

What About Commercial Colostrum Supplements?

A number of commercial products that act as colostrum substitutes are available. Research on these products conducted at universities indicate calves that received these products were healthier than those that received no colostrum at all; however, they did not receive the level of protection they would if fed frozen, stored colostrum.

What About the Risk of Johne’s Disease?

Johne’s disease (Myobacterium paratuberculosis) can be spread to your herd through infected colostrum. If you are using

colostrum from another cow as a supplement, be sure the cow from which you get it is free of Johne’s disease. (See NDSU Extension Service publication “Johne’s Disease in Beef and Dairy Herds” (V1209).

Be cautious about taking colostrum from other herds to use in your cow herd. Ideally, colostrum from your own herd is best because it will contain the immunoglobulins your calves need for disease protection. It also is the best way to guard against the spread of disease from herd to herd.

Calving Season Vaccinations

The goal of any vaccination program in a successful calving program focuses on the calf’s immune system. As mentioned in the colostrum management section, colostrum is the single most important factor in preventing disease in the very young calf. A good vaccination program utilizes the cow’s immune system (via colostrum) to protect the calf.

Cows should be vaccinated according to label recommendations to provide adequate protection. This allows the cow’s immune system to produce the antibodies the calf needs. Two doses are recommended to properly stimulate the cow’s immune system.

After the initial vaccination, a minimum of a yearly booster will be required to maintain the cow’s immune system every year to protect each calf. Following the labeled directions for every vaccine you use is very important. Different vaccines have different requirements to ensure their effectiveness.

Dozens of vaccines are marketed in the U.S. When used properly and in consultation with your veterinarian, almost all can be effective at reducing disease risks.

For Which Diseases Should You Vaccinate?

The answer is: those that exist in the local area. Your veterinarian will be able to advise you about the specific diseases in your locale.

The most common complaint at calving time is enteric (diarrhea) disease. It generally is the result of poor sanitation (muddy lots),

adverse weather conditions (cold and wet), and the mixing of sick and healthy animals (no hospital or recovery pens).

Sound management is vital to a successful calving season. A vaccination program alone will not protect your animals. Even the best vaccine can be overpowered by overwhelming numbers of bacteria, viruses and/or parasites. The most common enteric agents for which vaccines are available are rota virus, corona virus, Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp.

In a few herds, respiratory disease or even botulism can be a problem in young calves. Consult your veterinarian regarding these conditions.

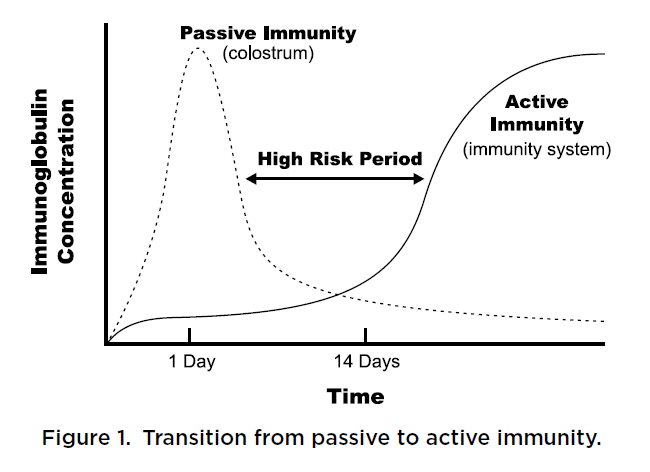

Often, these conditions will require vaccinating the cow before calving and then vaccinating the calf soon after calving. This can cause special problems. As shown in Figure 1, the colostrum the calf receives protects it from infectious agents, but it also will inactivate a vaccine.

If you vaccinate a young calf, you may have to revaccinate the calf at least once and maybe more until the calf is 6 months old. Involving your veterinarian is best if considering this type of program.

If you need to vaccinate a calf at a very young age, the best time to vaccinate it is the day it is born. The vaccine will have time to stimulate the calf’s immune system before the immunoglobulins the calf takes in by ingesting colostrum inactivate the vaccine.

A second dose of vaccine should be given at about 2 to 3 weeks of age, depending on the manufacturer/veterinarian’s advice, when immunoglobulins from colostrum are decreasing and immunoglobulins from active immunity are increasing.

Parasite Control

All adult cows should be treated for external parasites (lice). Adult cows are fairly resistant to internal parasites (worms).

Many herds can benefit from an internal parasite control program. This allows optimum nutrient utilization for the cow, decreases feed costs and maintains the cow’s level of immunity.

One of the best times to worm adult cattle is at weaning. If the cows are maintained in dry lot, they will not be reinfected until turned out on grass in the spring. If the cows are allowed to winter graze, they may reinfect while grazing and, depending on the parasite load, may need to be retreated during the winter.

Very young calves usually are not adversely affected by lice and worms. They are affected adversely by coccidia, cryptosporidia and giardia. These internal parasites cause diarrhea. They usually are associated with poor sanitation, wet environment, and mixing sick and healthy animals in the same pen.

No vaccines are effective against these pathogens. Medications are available to treat coccidia and giardia, but no medication is effective against cryptosporidia. Again, consult your veterinarian regarding management of these illnesses.

General Management

Providing a clean, dry area for cows that are calving and cow-calf pairs is critical to limiting the spread of disease in newborn calves. Calves born in muddy, damp pens or calves that nurse udders contaminated with fecal material are at increased risk for a number of disease conditions.

Bedding should be provided as needed to ensure that the animals have a clean, dry area that is free from mud and manure.

September 2017