Dry Edible Bean Disease Diagnostic Series (PP1820, Dec. 2016)

Root Diseases

Fusarium root rot

Fusarium solani

FIGURE 1 – Susceptible (L) and moderately resistant (R) bean varieties under heavy Fusarium root rot pressure

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Jessica Halvorson, Chryseis Tvedt, Julie Pasche, Bob Harveson and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Reddish-brown below-ground lesions

• Lesions may extend up the main root and hypocotyl

• Internal brown to red discoloration may be visible

• Yellow and stunted above-ground symptoms

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Cool and wet soils after planting

• Compacted soils and plant stress

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Soybeans and other pulse crops may be hosts

• May appear in circular patterns in a field

• Often found in a complex of other root rots

• Fungicide seed treatments may be effective early in the season

• Can be confused with other root rots and abiotic stresses

Pythium diseases

Pythium spp.

FIGURE 1 – Water-soaking symptoms on roots and hypocotyls (R) and healthy root (L)

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Wilting and death of a young bean plant

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – Pythium blight-phase causing necrosis of stems and petioles

Photo: J. Pasche, NDSU

SYMPTOMS

• Initial root rot symptoms appear as elongated, water-soaked necrotic areas on roots or hypocotyls, sometimes extending above soil line

• Wilting and death of plants (damping off)

• Symptoms on above-ground tissues (blight phase) may occur after extended conditions of rain, irrigation, high humidity or high moisture

• High levels of soil moisture

• Disease incidence often is greater where water accumulates in fields

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Cool-weather species (most active below 75 F) include P. ultimum, while warm-weather species (80 to 95 F) include P. myriotylum and P. aphanidermatum

• The pathogens survive in soil for years and can be moved with soil

• Any area of the plant in contact with the soil may become infected, resulting in water-soaked areas of the stem or upper branches (blight-phase)

• Can be confused with other root rots, wilts and white mold (blight-phase only)

Rhizoctonia root rot

Rhizoctonia solani

FIGURE 1 – Stunting, wilting and premature death

Photo: G. Yan. NDSU

FIGURE 2 – Sunken reddish-brown cankers

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – Brick-red discoloration in pith

Photo: J. Pasche, NDSU

AUTHORS: Jessica Halvorson, Julie Pasche, Bob Harveson and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Stunting and premature death of plants in field

• Lesions or cankers with reddish-brown borders on roots and base of stem

• Internal brick-red discoloration of pith

• Moderate to high soil moisture

• Cool, compacted soil

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Soybeans, sugar beets, potatoes, pulse crops and some weeds are hosts

• Often found in a complex with other root rots

• Fungicide seed treatments may help manage disease early in the growing season

• Can be confused with other root rots and abiotic stresses

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN)

Heterodera glycines

Photo: G. Yan. NDSU

FIGURE 2 – Small cream-colored females on dry bean roots

Photo: G. Yan, NDSU

FIGURE 3 – Stunting of pinto bean growing in pots with different levels of SCN; no SCN (C); 5,000 eggs/100cc (L); 10,000 eggs/cc of SCN (R)

Photo: S Poromarto, NDSU

AUTHORS: Julie Pasche, Guiping Yan, Berlin Nelson, Sam Markell and Bob Harveson

SYMPTOMS

• Plants can be infected with no above-ground symptoms

• Stunted or yellow areas of the field

• Small (1/32 to 1/6 inch) cream-colored and lemon-shaped cysts on roots

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Rotation with soybeans

• Light soil texture

• High soil pH

• Warm and dry soil

IMPORTANT FACTS

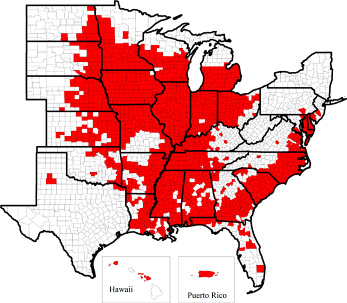

• Soybeans and dry edible beans are hosts

• Dirty equipment, flooding and wind erosion are SCN dispersal mechanisms

• All market classes are hosts

• Research indicates that kidney beans are the market class most susceptible to SCN and black beans are the least susceptible

Soybean cyst nematode soil sampling

Heterodera glycines

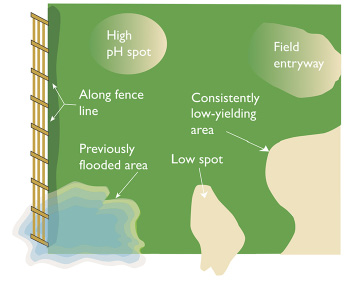

FIGURE 1 – High-risk spots for SCN

Courtesy Iowa State University

FIGURE 2 – SCN causing yellowing and stunting in kidney beans

Photo: G. Yan, NDSU

FIGURE 3 – Counties positive for SCN (detected on soybeans) as of 2014

Courtesy Iowa State University

AUTHORS: Sam Markell, Guiping Yan, Berlin Nelson, Julie Pasche and Bob Harveson

WHY SOIL SAMPLE

• SCN is a microscopic worm that lives in the soil and parasitizes roots

• Soil sampling is the most reliable way to detect SCN

WHEN TO SAMPLE

• In late summer/fall (before or after harvest), when SCN population is highest and more easily detected

WHERE TO SAMPLE

• Anything that moves soil can move SCN

• Concentrate sampling in areas where SCN is likely to be introduced or develop, especially field entrances

• Aim for the roots, dig 6 to 8 inches deep, take 10 to 20 samples, mix and send to a lab

WHAT RESULTS MEAN

• Results are presented as eggs/100 cc, which is the number of nematode eggs in approximately 3.4 ounces of soil

• Low levels (for example, 50 or 100 eggs/100 cc) could be false positives and should be viewed with caution

Stem and Wilt Diseases

Bacterial wilt

Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – Shriveled, orange-stained seeds (bottom) and healthy seeds (top) obtained from the same infected plant

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Bob Harveson, Sam Markell and Julie Pasche

SYMPTOMS

• Leaf wilting during periods of warm, dry weather or periods of moisture stress

• Interveinal, necrotic lesions which may be surrounded by bright yellow borders

• Seeds from surviving infected plants often will shrivel and be stained yellow or orange

• Very hot air temperatures (greater than 90 F), with wet or humid conditions

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Wilt pathogen survives in bean residue or seeds from previous year

• Infected seeds are primary mechanism of long-distance movement

• Wet weather, hail, violent rain and windstorms help the pathogen spread within and between fields

• Can be confused with root rots and other bacterial pathogens; foliar symptoms of bacterial wilt tend to be more wavy or irregular than common bacterial blight lesions and do not include water-soaking

Fusarium yellows (wilt)

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli

FIGURE 1 – Yellowing and wilting of leaves

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Permanent wilting and death of severely affected plants

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – Vascular discoloration of plants affected by Fusarium wilt

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

SYMPTOMS

• Foliar symptoms first appear as yellowing and wilting of older leaves, followed by younger leaves if the disease progresses

• Severely affected plants may wilt permanently

• Vascular discoloration of roots and hypocotyl tissues is primary diagnostic symptom; degree of discoloration varies in intensity depending on cultivar and environmental conditions

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• High temperature stress (greater than 86 F)

• Dry soil conditions

• Soil compaction

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Fusarium wilt often causes more dramatic symptoms than Fusarium root rot infections

• Unlike Fusarium root rot infections, Fusarium wilt seldom kills plants

• Death with wilt can occur before or after pod set

• Fusarium wilt can induce maturity two to three weeks earlier than normal

• Can be confused with other root rot and wilt diseases

Stem rot

Unknown sterile white basidiomycete (SWB)

FIGURE 1 – Wilting symptoms characteristic of SWB infection

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Small light brown lesions (L), moderate lesions (C) and large dark brown to black sunken lesions (R)

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – White mycelial strands of SWB and soil adhering to stems of infected plants

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Bob Harveson, Sam Markell and Julie Pasche

SYMPTOMS

• Wilting and death of young plants first observed after emergence

• On less severely affected plants, small lesions may be on hypocotyls

• Severe infection also can include sunken gray to black cankers on hypocotyls and stems

• White mycelial strands may grow over lesions or into stem piths; soil will adhere to stems when wilted plants are removed

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• High soil temperatures, but has been reported to cause disease from 60 to 95 F

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Thought to have many hosts

• Can survive at least one year in soils, likely in colonized residue of weeds or other susceptible crops

• Can be confused with other root rots, wilts and white mold

White mold

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

FIGURE 1 – Small tan mushrooms (apothecia) about ¼ inch in diameter emerge from hard, black structures (sclerotia)

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

FIGURE 2 – Enlarging tan lesions with white fungal growth

Photo: M. Wunsch, NDSU

FIGURE 3 – Mature stem lesion with dried-bone appearance, white fungal growth and black sclerotia

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

FIGURE 4 – Severe white mold damage

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Julie Pasche, Bob Harveson and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Water-soaked lesion that becomes tan as it enlarges

• Stem lesions will dry out, lighten in color and tissue may shred

• White fungal growth and hard black sclerotia may form in or on stem

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Wet soils prior to bloom; allows sclerotia to germinate and release spores

• Cool daytime temperatures (60 to 70F) during and after bloom

• Long periods of canopy wetness and/or frequent rainfall during bloom

• Lush plant growth

IMPORTANT FACTS

• All broadleaf crops and many weeds are susceptible to white mold

• Plants are only susceptible when in bloom

• Preventative fungicide applications may be economically viable

• Can be confused with wilt diseases or abiotic stress

Foliar Diseases

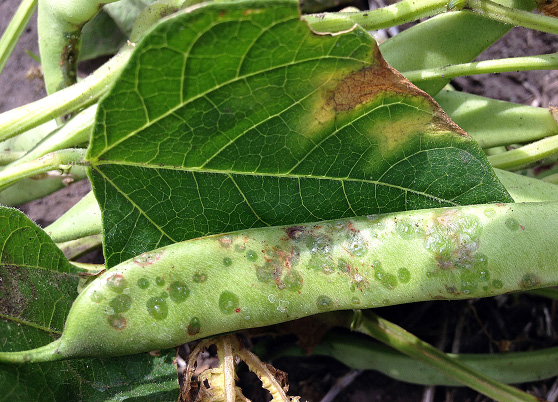

Anthracnose

Colletotrichum lindemuthianum

Photos: S. Markell, NDSU

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

AUTHORS: Jessica Halvorson, Sam Markell, Julie Pasche and Bob Harveson

SYMPTOMS

• Can occur on all above-ground plant parts

• Leaf vein and petiole lesions are dark and slender

• Pod lesions begin as small brown spots, enlarge to become circular and sunken

• Infected seeds may appear discolored and have necrotic lesions

• White fungal growth or cream-salmon-colored spore masses may be visible in lesions

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Infected seed

• Cool (55 to 80 F) temperatures

• Frequent rain or thunderstorms

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Pathogen is seed-borne and wind-dispersed

• Spread can occur by splashing water

• Pathogen can spread by animals, people or machinery moving through fields when foliage is wet

• Planting certified disease-free seed is best way to prevent the disease

• Can be confused with bacterial blights

Bacterial brown spot

Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 3 – Older lesions with holes after necrotic tissues fell out

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

SYMPTOMS

• Small, circular, brown lesions, often surrounded by a narrow yellow zone (not always present)

• Lesions may coalesce to form linear necrotic streaks between leaf veins

• Centers of old lesions dry and fall out, leaving tattered strips or “shot holes”

• May infect leaves, pods and seeds

• Warm air temperatures (80 to 85 F) with wet or humid conditions

• Storms that damage plants (hail, high wind)

• Planting infected seeds favors early infection and disease spread

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Pathogen survives in seed, residue and on other living hosts

• Wet weather, hail, violent rain and windstorms spread the pathogen

• Can be confused with other bacterial blights: necrotic area is similar in size to halo blight but smaller than common bacterial blight; yellow margin (halo) is narrow and bright as with common blight, but halo blight’s is larger, faint

Bean common mosaic

Bean common mosaic virus (BCMV)

FIGURE 1 – Mosaic, blistering and distortion (elongation) of leaves of affected plants

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Vein banding of leaves on an infected plant

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Bob Harveson, Julie Pasche and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Light and dark green mosaics and/or leaf malformation

• Downward rolling or cupping of leaves

• Vein banding, and stunting, necrosis or premature death

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Disease development dependent on susceptibility of cultivars and presence of aphids as vectors

• Yield losses more severe after early infections

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Type and severity of symptoms depend on host cultivar, virus strain and environment

• BCMV is spread among production areas by planting infected seed

• Several aphid species transmit BCMV

• More than 10 strains of BCMV are known

• Can be confused with other viruses, herbicide damage or plant stress

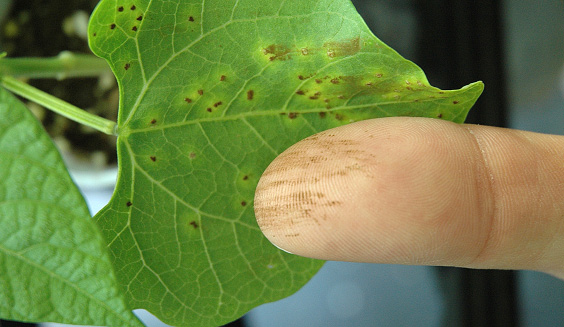

Common bean rust

Uromyces appendiculatus

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Cinnamon-brown (uredinia) and black (telia) rust pustules

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

FIGURE 3 – Dusty cinnamon-brown spores rubbed off pustule with yellow halo

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

AUTHORS: Sam Markell, Bob Harveson and Julie Pasche

SYMPTOMS

• Small (1/16 inch) cinnamon-brown pustules that may have a yellow halo

• Pustules turn black at end of growing season

• Usually first observed in areas of a field with concentrated infection, called “hot spots”

• Close proximity to a field that had rust the previous year

• Frequent heavy dews

• Moderate to warm temperatures (65 to 85 F)

• Factors favoring wet microclimates: lush plant growth, close to shelter belts, etc.

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Pathogen is specific to edible beans

• Infection may occur at any time and spread very quickly

• Fungicides applied after detection may be economically viable

• Pathogen has different races, which may overcome resistance

• Can be confused with soil splash, brown spot and halo blight

Common bacterial blight

Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli

FIGURE 1 – Large necrotic lesions with narrow yellow borders

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

FIGURE 2 – Severely damaged leaves appearing burned or scorched

Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

AUTHORS: Bob Harveson, Julie Pasche and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Leaves, pods and seeds can be infected

• Initial symptoms: small water-soaked spots on the underside of leaves

• Spots enlarge and coalesce to form large necrotic areas with a narrow, bright yellow border

• Severely damaged leaves appear burned and remain attached at maturity

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Warm air temperatures (80 to 90 F) with wet or humid conditions

• Storms that damage plants (hail, high wind)

• Planting infected seeds favors early infection and disease spread

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Bacteria survive in fields on infected seed or bean tissues

• Pathogen can spread by animals, people or machinery moving through fields when foliage is wet

• Can be confused with anthracnose (pod infection) and bacterial diseases; yellow margin (halo) is similar in color and brightness to bacterial brown spot but necrotic area is larger

Halo blight

Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola

FIGURE 1 – Small water-soaked spots on underside of leaf

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

FIGURE 2 – Broad yellow-green halo surrounding small necrotic spot

Photo: J. Pasche, NDSU

FIGURE 3 – Severe infection and the beginning of a systemic chlorosis in plants

Photo: R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

AUTHORS: Bob Harveson, Julie Pasche and Sam Markell

SYMPTOMS

• Begins with small water-soaked spots that become necrotic

• Broad yellow-green halo may develop around necrotic spots

• In severe cases, a general systemic chlorosis may develop in infected plants

• Also may infect pods and seeds

FACTORS FAVORING DEVELOPMENT

• Cool air temperatures (68 to 72 F) with wet or humid conditions

• Planting infected seeds favors early infection and disease spread

• Storms with high winds, rain or hail will damage plants and spread pathogen from plant to plant

IMPORTANT FACTS

• Yellow-green chlorotic halo more pronounced at cool temperatures, less noticeable above 75 F

• Pathogen can spread by animals, people or machinery moving through fields when foliage is wet

• Can be confused with other bacterial blights; necrotic area is similar in size to bacterial brown spot but halo is much larger and a fainter yellow-green

December 2016